Introduction

Revisiting our back pages brings Cold War chills and thrills

Twenty years ago this December, the Soviet Union went kaputski. It seems hard to believe it’s been that long since the “evil empire,” whose leaders once boasted they’d bury the West, was shoveled out onto the ash heap of history.

An entire generation of Americans has grown up without fearing the “red menace” or even jeering those seemingly unnaturally-imposing Olympic athletes in the “CCCP”-emblazoned uniforms.

What do the youngest generations make of the serious 1950s-60s Civil Defense films showing how to “duck and cover” — in case the “atom bomb explodes right now”? Viewed on YouTube, they now seem as absurd as the black comedies of their day, like “Dr. Strangelove,” or the surrealistic humor in early Bob Dylan songs, like his “crazy dream” of World War III: “I lit a cigarette on a parking meter and walked on down the road.”

Into that Cold War period, this publication came along. Then known as Indiana Rural News, the first issue was produced for July 1951.

Throughout its 60 years, your Indiana electric cooperative publication has remained dedicated to bringing readers news and information about their cooperative, the electric industry, safety and efficiency. But it also has included general interest features about rural Indiana, consumers, their culture and lifestyles, Indiana destinations, history and more.

In the 1950s and 1960s, that included covering new businesses and electric consumers that catered to the Cold War needs, be it bunkers burrowed into hillsides or military missiles bunkered in the meadows, or community projects that lifted our eyes skyward. Some stories outlined U.S. Department of Agriculture booklets pointing out the need to safeguard crops and animals from radioactive fallout.

This month, to celebrate the anniversaries of our beginning and the Cold War’s end, we set the “wayback machine” to 1952, 1961 and 1963 to bring you three blasts from the past: stories from the early days of this publication. We visited sites related either directly or indirectly to these stories to see how the years and the changing world landscape changed them.

Part 1: Failed Safe

‘Toward a confident future” says the cover slogan on the 1968-circa sales brochure for the microfilm depository. But a composite photo of a mushroom cloud billowing above New York City — in black and blood red duotone — is one of the first images inside beside the words: “Are you prepared to face disaster?”Ominous? Yes. But with 40 years hindsight, the brochure foreshadowed only the fate of the company it touted. The depository disappeared by the mid-1970s. Left behind are the crypt of a Cold War-curiosity … and a cryptic tale entangling one of the most grisly, unsolved murder cases in Indianapolis history.

Bunker in Burrows

The depository was a vault burrowed into a remote hillside near Burrows, a small burg in Carroll County, in 1960. Clem Corporation, a father-son company from Logansport, initiated the enterprise. The son, a World War II vet, had developed the idea several years earlier. The company was named after the family dog because, as the father explained in a November 1960 Delphi Journal news story, “dogs have the good sense to bury their bones.”Had the Cold War with the Soviet Union ever turned hot, apparently the modern, good-sense way to protect vital records from atomic blasts and radioactive fallout was to bury them in the man-made, self-subsisting, climate-controlled bunker.

The depository was a vault burrowed into a remote hillside near Burrows, a small burg in Carroll County, in 1960. Clem Corporation, a father-son company from Logansport, initiated the enterprise. The son, a World War II vet, had developed the idea several years earlier. The company was named after the family dog because, as the father explained in a November 1960 Delphi Journal news story, “dogs have the good sense to bury their bones.”Had the Cold War with the Soviet Union ever turned hot, apparently the modern, good-sense way to protect vital records from atomic blasts and radioactive fallout was to bury them in the man-made, self-subsisting, climate-controlled bunker.

The company rented out storage drawers in the bunker, much the same way safety deposit boxes are rented in banks. Microfilm of important documents, records, blueprints and secret formulas were kept there. Clients included drug makers, an electronic missile contractor, various government entities, regional banks, insurance firms and, reportedly, even the Coca-Cola Company.

The vault featured 18 inch steel-reinforced concrete walls. The depository room was 96 feet long and 16 feet wide with an arched ceiling 14 feet high. Two rows of file cabinets lining the room provided 4,500 file drawers for holding the boxed and cataloged rolls of microfilmed records. The room was protected by a 1.5 ton radiation-proof steel and lead door and equipped with two gamma-ray detectors to measure radioactivity inside and outside the secluded facility.

Manned 24/7 by a guard, the vault also was equipped with a large standby generator, capable of running the systems for up to a month; a stove; sink; refrigerator; toilets; bunks; and a 90-day supply of food for five people.The facility was served electrically by Carroll County REMC. The Indiana Rural News featured the venture, “Safeguarding Records in the Atomic Age,” in the March 1961 issue.

The location for the vault was chosen with the help of the federal government using maps of air movements from strategic areas in the region that the Soviets would target. Jim Powlen, who now owns the two-acres of land with the vault, chuckles at the choice. “They thought they were away from a nuclear threat. Grissom [air base] is 18 miles from here. Where’s the first place you’re going to bomb?” he asked rhetorically. “Grissom.”

The land was originally owned by an aunt of Powlen’s wife. She traded it to the developers for a share in the partnership. Clem Corporation had an option on an additional 542 acres nearby for future growth, which included plans for an air strip to more quickly fly records and microfilm in or out.

Shortly after the vault was completed, Powlen and his wife, Lois, who died in 2008, built their house just down the road and up the hill from the vault’s entrance and began raising their family.

Microfilm and murders

In 1967, Clem Corporation sold the vault to a newly-formed company, Records Security Corporation. RSC, as it called itself, became involved in not just securing microfilm at the vault but in all aspects of the growing microfilm industry. It opened an Indianapolis office in 1968.

Then, on Dec. 1, 1971, the story of the Cold War vault turned into a tragic, chilling suspense thriller. That’s when two former RSC employees and a third man were found dead in the Indianapolis bungalow the two shared on LaSalle Street.

Dead were: Bob Gierse, 35; Bob Hinson, 27; and Jim Barker, 26. The three strapping bachelors were found beaten and gagged. Their hands and feet were bound with strips of bed sheets. Their throats were slashed from ear-to-ear.

Gierse had been RSC’s executive vice president/general manager and Hinson was a production manager. Both, reportedly, made trips to the Burrows vault. But earlier that fall, both left RSC to form their own microfilm company. Barker sold microfilming equipment for Bell & Howell. All three had previously worked for Bell & Howell in Chicago.

Multiple angles for the crime emerged as police uncovered the reckless professional and personal lives the men led. The three were notorious, hard-drinking playboys who didn’t back down from fights at the seamy bars they frequented.

Police checked out husbands and boyfriends of their many lady “friends,” and a man Hinson bloodied in a brawl the weekend before. Their former employer, the president at RSC, was also a suspect; the company still held life insurance policies on Gierse and Hinson totaling $150,000. The policies were set to expire in 10 days when the murders occurred; and the RSC president had phoned Gierse and Hinson twice from his Jasper, Ind., home the night of the murders. He told police it was to discuss business.

Police also focused on what the three might have known about two other unsolved murders in Indianapolis earlier that year. One victim was a microfilm business acquaintance; the other was a known thief who was an acquaintance of at least one of the three. Both of these men were found shot execution style. In addition, the Indianapolis newspapers reported at the time that, while searching for clues, police uncovered stolen property at the microfilm business Gierse and Hinson started. One item was a piece of microfilm equipment belonging to RSC that Gierse himself reported stolen months before while he was still RSC’s executive vice president.

Indiana State Police at the time said the murders had all the markings of organized crime. Speculation included the Chicago mob which might have been trying to infiltrate the microfilm business and made an example of the men. Perhaps Gierse and Hinson turned down an offer they should not have refused, or owed a debt they had not repaid.

Other speculation involved what they might have microfilmed and who might have wanted it. Coincidentally, or maybe not, a burglary was reported to police the night before the murders at the vacant house formerly shared by Hinson and Barker — before Hinson moved in with Gierse on LaSalle Street and Barker moved into his own place.

Though the only evidence left at the crime scene was a bloody boot print, police theorized the killer, or most likely killers, waited for Gierse and Hinson in the home on the evening of Nov. 30, 1971. When the men arrived separately at different intervals, each was probably immediately jumped, beaten and bound. Police said Barker, who arrived last, might have been simply at the wrong place at the wrong time. Police theorized the three were then slain. Gierse was found on his bed in the back bedroom; Hinson was found on his bed in the front bedroom; Barker was found on the bathroom floor between the bedrooms of the modest, two-bedroom home.

In Burrows, Powlen, now 74, said the scuttlebutt was the victims had gotten into records they should not have seen. He recalls the reaction of the woman running the vault when the murders were discovered. “She came up here white as a sheet,” he recalled, sitting in his living room.

“Whatever you do, if anyone asks questions, don’t give them my name, and tell them to call the sheriff’s office,” she told the Powlens.

“They were afraid there might be repercussions,” he said. “To my knowledge, that was the last day she was there.”

Only one person, the ex-husband of one of the lady friends, was ever indicted for the crimes. That came in 1996. The 20th anniversary of the murders in 1991 brought renewed media interest and investigations. The man, an original suspect who was questioned in 1971, was never tried, however. The case collapsed after the accuser, an alleged accomplice serving time for murder in Florida, not only recanted his confession but implicated President Richard Nixon and labor boss Jimmy Hoffa in a conspiracy tale of microfilm and political espionage. (see footnote below)

Nail in the coffin … closing of the crypt

Here’s where the vault’s “microfilm trail” spins from the reel. Most of the principal characters are either now deceased or unable to recall details because of age and illness. What happened to the microfilm stored in the vault and what happened to RSC after the murders is not clear. Electric Consumer contacted a half dozen people close to the story, including the relatives of the suspected former RSC president, who died a decade ago, and his secretary-treasurer who was the woman working at the vault the day of the murders.

Though records show RSC remained a consumer in good standing with Carroll County REMC until RSC closed its account in 1973, Powlen said he believes the doors at the vault never reopened after the murders. RSC’s local address for the vault was listed as only a post office box in Logansport. Its Indianapolis office was listed in the city directory through 1973.

Besides the effect of the murders, other reasons for RSC’s demise could include:

• Financial — Before the murders, RSC was sued for $20,000 damages by two former associates over rights to microfilm equipment they claimed to have invented;

• Obsolescence — By this time, the nuclear arsenals of the Soviet Union and United States had grown so large and lethal, trying to survive or safeguard anything from a nuclear exchange under the doctrine of “mutual assured destruction” seemed futile, if not absurd.

Putting the “when, wherefores and whys” aside, once the vault did close, Powlen noted, “The thing just sat and sat and sat.”

Abandoned for four years, the vault went up in a county tax sale in December 1976 and was purchased by local attorney Lewis Mullin. His son, Bill, said Mullin paid only a small amount because no one wanted it. Mullin removed the file cabinets, office furniture and other items — and then resold the property. Bill Mullin said he has no recollection of any of the microfilm that had been stored there remaining in the vault when his father took possession.

Powlen said subsequent owners stripped the remaining valuables, including the “humongous” standby generator. One owner tried to raise earth worms there; another tried to store furniture. By 1989, REMC records show the electricity was shut off for good, and the earth began to reclaim the dark, dank shell.

In 1990, a real estate agent representing the vault’s owner at the time called the Powlens one Friday night. The owner was in a bind and needed cash fast. He wondered if the Powlens were interested in buying the property. Powlen said he offered a fair value for the two acres of land, but it was nowhere near the asking price. The next morning, though, the agent called back and asked if Powlen could get the money by noon. Powlen did, and the land came back into the family.

In the meantime, the empty vault became known to area teens who occasionally used it as a secret hang out. Drug use and drinking in the vault became evident. Trespassers covered the walls with graffiti and smashed one of the remaining porcelain toilets. Worried about the liability, Powlen sealed the vault shut in the early 2000s.

The vault — built to secure records through the ravages of time and the most feared cataclysm of the Cold War — ironically failed to last a dozen years. Had the arms race in the Atomic Age made it obsolete so soon? Or was this safe’s “confident future” cracked by the same sins afflicting humankind since the stone age?

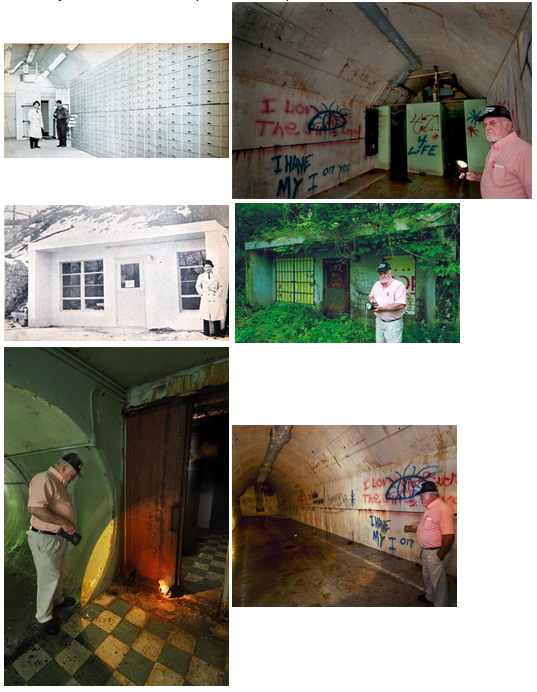

PHOTOS

Then and now: From the pages of the March 1961 electric cooperative publication (left), Robert Clawson, then manager of Carroll County REMC, stood with J.O. James, head guard at a new subterranean vault that featured 4,500 file drawers to safeguard important records in case of nuclear war. Standing in almost the same spot 50 years later, REMC consumer Jim Powlen, who now owns the land and structure, looks over the graffiti covering its walls. After the records storage business was shuttered around 1973, the crypt-like vault was eventually abandoned and heavily vandalized.

The entrance through an office front is along a county road. A tunnel then leads back to a secondary chamber where the bunks were located to the right, and, to the left, behind the almost 2-ton steel and lead door that still stands on wheels, rusting away in its tracks, is the 96-feet long vault room. The door to the facility was sealed for liability issues.

Part 2: Missiles in the Meadows

Rural Indiana hosted Nikes to defend cities and industrial areas

The end wasn’t supposed to come like this: a sneak attack by small bands of Soviet special forces on U.S. missile bases in the heartland. But here they were in the spring of 1972: Soviet Spetsnaz battling surprised U.S. troops under a gray cloud cover rolling off Lake Michigan.

Create chaos in U.S. air defenses, and the coordinated ground assault might open U.S. skyways to Soviet bombers and nuclear missiles. The hammer and sickle would strike a crippling first blow in the final conflict.

But the rat-a-tat-tat firing from weapons in this battle splattered only marble-sized capsules filled with colorful dye — paintballs — not blood.

The scenario, called “Red Strike!,” played out over a weekend last month just for fun at Blast Camp, a paintball field north of Wheeler. The apropos storyline was compelling, but not as much as the field itself. As described in the promotional material, Blast Camp is an actual former U.S. Army Nike missile base.

The scenario, called “Red Strike!,” played out over a weekend last month just for fun at Blast Camp, a paintball field north of Wheeler. The apropos storyline was compelling, but not as much as the field itself. As described in the promotional material, Blast Camp is an actual former U.S. Army Nike missile base.

“I was so confused …” said Stan Dziaba. “Missile base? I had no idea there were missile bases anywhere around Chicago.”

The 22-year-old paintball enthusiast and Steuben County native was joined by his younger brother and two other Loyola University buddies down from Chicago for the first time at Wheeler. “The whole draw was the missile base,” he said.

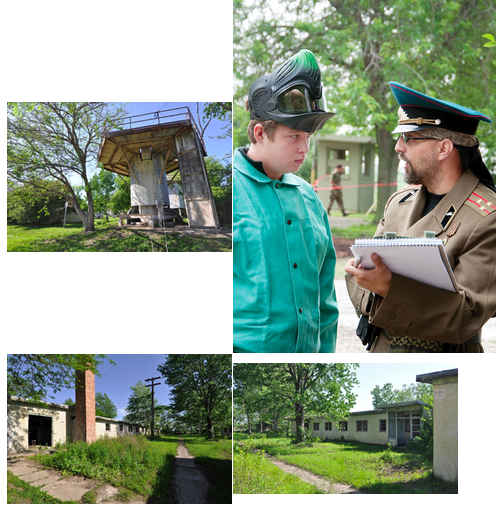

Blast Camp includes the original 21 acres, 17 buildings, and five radar towers that made up the control and guidance section of the missile battery known as C-47. Active from 1954-1972, the base was among the first to deploy nuclear missiles. The site became a paintball field in 1988. Virgil Frey, owner and operator, bought the business in 2009.

“I’ve been around the area all my life,” the 40-year-old Frey said. “Like quite a few people that I’ve talked to since I’ve owned it, I never even knew it was there.”

Named after the Greek goddess of victory, Nike was the nation’s first radar-guided surface-to-air missile system. Deployment began in 1953. The bases, some 300 in all nationwide, were top-secret, tightly-secured and key to the U.S. doctrine of deterrence.

The batteries ringed large cities, industrial areas and other military installations. They were the last-ditch defense designed to destroy incoming Soviet bombers and ballistic missiles before they could deliver their devastating nuclear payloads.

Two-dozen bases encircled the Chicago-Gary area which included industrial northwest Indiana and southern Michigan. Five of these bases were in Indiana.

A sixth Nike base was located in southeastern Indiana near Dillsboro as part of the Cincinnati-Dayton defensive ring. That site, served electrically by Southeastern Indiana REMC, was featured in the March 1963 Indiana Rural News.

The missile batteries were broken into two areas usually separated by a short distance: a launch site where the supersonic missiles were assembled and stored horizontally in underground bunkers or “magazines”; and the control and guidance base which also served as the post for the 140-200 soldiers stationed at the base.

While remnants of the other Indiana sites still exist, C-47 is the only base fully intact. That’s rare nationally, too. It’s listed on the National Register of Historic Places. For many years, the site was owned by the Portage school system, which is one reason it was so well preserved, Frey said.

The C-47 launch site is about a mile from Blast Camp. It’s bordered by fields and a county road, and is concealed by brush and trees surrounding the perimeter fence. The 14-acre site still includes the guard shack, several buildings and the concrete pad with large metal blast doors covering the three magazines. The magazines flooded with ground water after the pumps were turned off when the site was decommissioned.

The site near Dillsboro, CD-63, is now the private residence of Harold Whisman, a Southeastern Indiana REMC consumer. He transformed one of the underground magazines into his home in 1979. He still uses half of the elevator, previously used for moving missiles to the surface, to bring his Corvette or other classic cars down into his family room. The 14.5-acre site was set up in 1958 and closed in 1969. It is thought to be the only missile site in use as a residence.

In the late 1960s, Soviet development of intercontinental ballistic nuclear missiles with multiple warheads reduced the effectiveness of Nike defenses. They were among the anti-ballistic missiles phased out in the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty between the U.S. and Soviet Union. All operational Nike sites were deactivated by 1974.

This American history, right here in our backyards, isn’t lost on Frey at Blast Camp. He plans to share more of the base’s story with the public, including an open house and World War II re-enactment the weekend of Aug. 13-14. A small museum inside a planned pro-shop at the field will be dedicated to preserving the site’s history. “We don’t just play paintball out there,” he said. “Even though it is about family and fun and playing paintball, the memorial of the base is such a huge piece to what we do.”

Standing at Blast Camp, visitors can look to the northeast across a mile of open farmland and see the brush lining the remains of C-47’s launch site. It’s sublime to think all this was once a place where nuclear Nikes were ready to be fired into those gray skies above to defend our country.

Taking it in, Donnie Arndt, another of the Loyola University students in for “Red Strike!” echoed a universally-held thought … just before he and his comrades lowered their face shields and entered the field of play. “Thank God,” he softly mused, “they never had to be used.”

PHOTOS: A groundskeeper mows just beyond a disarmed Nike Ajax missile erected as a memorial to the Cold War years at the William Powers Fish and Wildlife Area on the Illinois side of Wolf Lake. The lake straddles the state line just south of Lake Michigan.

Metal doors of the C-47 missile launch site north of Wheeler rust in place, covering the underground magazine where defensive nuclear-tipped Nike Hercules missiles were ready to fire. The bunker is now flooded with ground water. Left: A mile away, the C-47 control area, which has all the original buildings including the guard shack in the background, is now a paintball field. An event in June pitted Soviet special forces against the U.S. base.

Playing the role of the Soviet commander is Victor Morris, right, of Longview, Texas, as he goes over battle plans with one of his Spetsnaz, 13-year-old Gabe Tilford.

Part 3: All Along the Watchtower

Volunteers kept watch for enemy bombers at nation’s first ‘Skywatch’ tower

The nuclear family (right) stands hand-in-hand, gazing stone-faced toward the sky, ever vigilant for enemy bombers.

The nuclear family (right) stands hand-in-hand, gazing stone-faced toward the sky, ever vigilant for enemy bombers.

That’s the takeaway image that remains unchanged at the tiny burg of Cairo where the nation’s first “Operation Skywatch” tower was commissioned early in the Cold War.

That’s the takeaway image that remains unchanged at the tiny burg of Cairo where the nation’s first “Operation Skywatch” tower was commissioned early in the Cold War.

Operation Skywatch was a civilian volunteer program of the U.S. Air Force. It began in 1950 to fill in the gaps in coverage in the nation’s nascent radar defense system to guard against air attack by Soviet bombers. Volunteers in the Civilian Ground Observer Corps at Cairo, just north of Lafayette, stood watch 24/7 and would report to the Air Force relay center in South Bend whenever they’d spot an aircraft they could not positively identify as “friendly.”

Some 90 to 120 individual volunteers participated in the program, each taking a two-hour shift every six days. Cairo at the time, by the way, had a population of just 25 people.

The post was organized by Cairo’s grocer, Larry O’Connor, a retired Navy chief petty officer in 1950, at the request of the Air Force. The story of how the community came together to build the program’s first formally commissioned tower, known as Delta-Lima 3-Green, was featured in the October 1952 Indiana Rural News, “Cairo goes into Action.” The commissioning ceremony took place Aug. 16, 1952, and was attended by 500 people.

Before the tower was built, volunteers gathered on top of O’Connor’s brooder house behind the grocery. They soon realized they needed something higher and more substantial than a chicken shed to stand on. The tower was planned and built from donated materials and labor from around the area. Tipmont REMC donated utility poles for the four main corner timbers of the framework and the use of a truck to set the poles.

The tower was topped with a 12×12-foot railed observation deck. Centered on the deck was a covered 7×7-foot shanty, with a desk, chair, telephone and electric clock.

The tower was topped with a 12×12-foot railed observation deck. Centered on the deck was a covered 7×7-foot shanty, with a desk, chair, telephone and electric clock.

Nationwide, Operation Skywatch at its zenith enlisted over 800,000 volunteers at over 16,000 posts and 75 relay or “filter” stations. After the Korean War, the program was phased out. The Cairo tower was decommissioned in 1954.

For the U.S. Bicentennial in 1976, the tower was reconstructed at its original site and the statue of the family was commissioned to be sculpted. The statue was installed at the site in May 1980.

In his 2002 book Oddball Indiana, travel writer Jerome Pohlen noted the tower was one of his favorite off-beat places in Indiana, and quipped in a caption beneath a photo of the aging tower, “Let’s see the Russkies get past THIS.”

Even though the reconstructed tower is now crumbling, slowly shedding its splintered weathered boards piece by piece into the tall grass below, who’s to say the original — along with its corps of civilian volunteers — wasn’t an effective deterrent? After all, 60 years later you’re able to read this, and our cities, our nation and our freedoms are all still here.