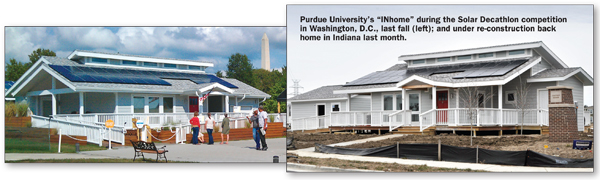

Five months ago, this “Indiana Home” in Lafayette was gleaming — but not in the moonlight upon the nearby Wabash. Rather, the cute clapboard bungalow new to Shenandoah Drive basked in the sunlight upon the Potomac — amid memorials and monuments in the nation’s capital — and in the glow of national praise. Dubbed “INhome” for short, the house was Purdue University’s entry in the U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Decathlon in Washington, D.C.

The collegiate competition, held every two years, judges solar homes as they’re put through the energy-gulping rigors of daily life in a series of 10 categories. These include such things as energy efficiency, cost, comfort and market appeal. The event was staged at a park near the Jefferson and Roosevelt memorials, Sept. 23-Oct. 2, 2011.

Each house was to be “net-zero” for energy consumption. That meant it had to produce at least as much energy as it used over the competition. The houses had to rely on the solar power they collected for everything from heating and cooling to lights, hot water and appliances.

Purdue placed second overall among 19 entries. The University of Maryland placed first. Other entries from the Midwest included Ohio State, fifth, and the University of Illinois, seventh. International teams included New Zealand, which placed third; Canada; Belgium and China.

What set Purdue’s place apart from all the others in the competition was that INhome is a darling little dynamo — rated to generate up to 17 percent more electricity than it should use — cloaked within a sensibly attractive design. INhome, the Purdue team noted, offers a “realistic and balanced vision for ultra-efficient housing.” The blend of technology with functional aesthetics demonstrates how folks can live sustainably without sacrificing quality or comfort.

What set Purdue’s place apart from all the others in the competition was that INhome is a darling little dynamo — rated to generate up to 17 percent more electricity than it should use — cloaked within a sensibly attractive design. INhome, the Purdue team noted, offers a “realistic and balanced vision for ultra-efficient housing.” The blend of technology with functional aesthetics demonstrates how folks can live sustainably without sacrificing quality or comfort.

“What we really liked about showing in D.C., we were one of the few non-architectural schools there,” said Eric Holt, a Purdue doctoral student and construction manager for the project. “Architectural schools did architectural statements — ‘house of the future’ type stuff. It was very futuristic. Ours had a very mass appeal. It looked like a real house — to show people you didn’t have to live in a spaceship to have a solar, net-zero home.”

The homey appearance made Purdue’s entry a favorite in the competition among the 300,000 people who strolled through the homes during the 10-day run. It was the only entry in the DOE’s five competitions, starting back in 2002, to ever include a garage.

By contrast, one team’s abstract structure this past competition was covered almost entirely with a thick quilt of insulation wrapped in white, vinyl-coated fabric. It looked more like something folks would see at a space shuttle exhibit in the Smithsonian up the street than on the street where they live.

“I’ve looked at the 70-80 homes that have been done over the last 10 years,” said Kevin Rodgers, a Purdue grad student who served as project manager. Only one other decathlon home, he found, is being used in a community — and that’s as an artists’ studio. “Most don’t fit into neighborhoods.”

Now, back home, INhome has been rebuilt on the edge of an older established neighborhood as part of a subsidized redevelopment project where once stood crime-ridden apartments. While the home is the only stand-alone house in Lafayette’s new Chatham Square neighborhood, its size and design fit nicely with the other green and energy-conscious duplexes and quadriplexes.

“This is the only one I consider in a traditional neighborhood,” added Rodgers. “That was the long-term goal: This house wasn’t going to be scrapped; this house wasn’t going to just sit on a university backlot.”

Shining bright

Purdue began the decathlon project in 2009. That’s when Rodgers and five other colleagues went to Washington to scout out that year’s competition. They came home and, with faculty and staff, began to blueprint their two-year course of action for the 2011 event. Along the way, Purdue also received support from Indiana industries and businesses.

A core team of 15-20 students, and more than 200 students in all, worked on the project through 2010 and 2011. The project brought together six colleges and schools within the university and 15-20 departments. Several 500-level courses were created just for the project, while other aspects, including signage and displays to accompany the open house/public education aspect of the decathlon, were incorporated into existing courses.

A core team of 15-20 students, and more than 200 students in all, worked on the project through 2010 and 2011. The project brought together six colleges and schools within the university and 15-20 departments. Several 500-level courses were created just for the project, while other aspects, including signage and displays to accompany the open house/public education aspect of the decathlon, were incorporated into existing courses.

“We did what’s called ‘integrated design,’” said Rodgers. “That’s basically where your designers, architects, interior designers, engineers, construction disciplines all get together and plan at the same time — which seems like ‘duh,’ but it actually doesn’t happen that often in the industry.”

Decathlon rules stipulated that the total interior floor area of a house could not exceed 1,000 square feet. Purdue’s home came to 984 square feet, about the size of a two bedroom apartment or a vacation-style condo.

The front door opens to a living/dining/kitchen area with a bar. The home has a large bathroom and a utility room. In the back of the home are two bedrooms. A deck that surrounds almost the entire home extends the living space to the outdoors while vaulted ceilings with windows give the home a bright and airy feel.

The front door opens to a living/dining/kitchen area with a bar. The home has a large bathroom and a utility room. In the back of the home are two bedrooms. A deck that surrounds almost the entire home extends the living space to the outdoors while vaulted ceilings with windows give the home a bright and airy feel.

Instead of using standard wood-stud construction, INhome utilizes high-efficiency structural insulated panels for the walls and ceilings which were donated by Thermocore based in Mooresville. The tongue-in-groove panels helped ensure the home’s thermal envelope would be airtight and well insulated, greatly reducing the biggest energy draw on any home: heating and cooling. This follows the same philosophy as the Indiana Touchstone Energy Home Program.

Holt, a former Tipmont REMC consumer who built homes in the Lafayette area for 19 years before returning to Purdue for his master’s and now a doctorate degree, credits the panels for helping INhome tie for first in the Energy Balance category and place second in both Affordability and Comfort Zone aspects of the decathlon.

What’s more, the Thermocore panels were more structurally rigid than standard construction. This was needed for the home’s unconventional pedigree. INhome was initially built on the West Lafayette campus. Then it was disassembled and reassembled once just for practice; then disassembled and trucked to Washington.

“We’re probably the only team that practiced tearing it apart and putting it back together before we actually went to the competition,” Rodgers said.

“We’re probably the only team that practiced tearing it apart and putting it back together before we actually went to the competition,” Rodgers said.

“It was very important for our team to know that we could do it ahead of time and get it done,” noted Holt. “There were still hiccups along the way in D.C., but at least we went in with the confidence that, ‘hey, we’ve done this before, so no matter what comes up, we can get it done here.’”

Once in D.C., each team had seven days to put its house in order. Purdue’s homey design didn’t lend itself easily to that kind of mobility. Said Rodgers, “If you look at past competitions, some were very long and rectangular, and they were easy to pull down the road. We didn’t really want that feeling. So we designed it first and worried about transporting it later.”

To get it to Washington, the single-level home was split into six pieces: three core sections that were then cut in two at the eight-foot level separating the walls and floors from the vaulted ceilings and roof. Some 1,400 screws were used to hold the modules together.

Twenty-seven SunPower solar panels cover most of the sloping south-facing roof while nine more, turned toward the sun, peak up over the roofline from the north side. An inverter converts the panels’ power to AC to run the home. As it turned out, seven of the 10 days of competition were cloudy. Still, the PV panels provided more energy than Purdue’s home needed.

To make sure the PV panels, which could produce over eight kilowatts, could provide all the electricity needs, Purdue’s home is equipped with:

• a Trane high-efficiency air-to-air heat pump;

• a GE heat pump water heater;

• high-efficiency GE appliances;

• a mechanical ventilation system with a multi-process air purification system, including a self-watering biowall, to remove airborne contaminants.

All told, the cost of construction came to $257,000. In the redeveloped neighborhood, a subsidized owner is expected to move in later this year. Rodgers and Holt said they expect the home to be marketed to younger professionals or perhaps retired empty nesters. But someone, they agreed, is going to get a great deal on a home that will also generate some excess cash from any surplus electricity that can be sold back to its electric utility — Duke Energy, in this case.

Back home again in Indiana

As soon as the finishing touches are complete at its final location, INhome will be opened to the public March 31. It’s being considered, too, for a parade of homes this summer. After that, a homeowner will move in. But that won’t be the end of the project. Purdue will remotely monitor the home’s performance with real-world, in-use data for further research for the next five years.

In addition, Holt will be writing his doctorate dissertation on the home’s “educational footprint.” “We’ve got so much time and effort involved in this, so many students involved in it, that we wanted to show what educational impact is made,” he said.

In addition, Holt will be writing his doctorate dissertation on the home’s “educational footprint.” “We’ve got so much time and effort involved in this, so many students involved in it, that we wanted to show what educational impact is made,” he said.

Already, some six master’s or doctorate degrees have been based on the house and the data it has provided. Rodgers noted that the project has also gotten more students thinking about careers in housing. “It’s tough to convince young people to get into this industry, so this was a really great project to do that. It’s already changed a few career paths for students.”

Rodgers said the project has given him a broader picture about balancing budget with sustainability. INhome is a starting point for the future. “We’ve got to do something,” he said. “The housing markets crashed. The McMansions … 5,000 square feet … people don’t want that anymore. Suburbs are kind of falling to the wayside. And buildings use 40 percent of the energy in the U.S. It’s huge. It’s bigger than transportation. It’s bigger than the industrial sector. Most people don’t realize how much an impact the housing market makes.

“We were trying to show them that you can do it slightly different and really make an impact,” Rodgers said.

For more information on the competition, please visit these websites: http://www.solardecathlon.gov; andwww.purdue.edu/inhome/.

Photos by the U.S. Department of Energy and Richard G. Biever