By Richard G. Biever

At 6-feet-4, Alonzo Fields could look over the shoulder of most people. But none were as broad as those of the four men he served as the chief butler in the White House for 21 years.

Born in the tiny Black farming community of Lyles Station in southwestern Indiana in 1900, Fields stood beside Presidents Herbert Hoover, Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and Dwight Eisenhower. From 1931–1953, through the Great Depression, World War II, and the beginning of the Korean War, few other men stood so near to so much White House history as it unfolded.

“People don’t realize when this man from Lyles Station was actually in the role as that chief butler, he was exposed to every secrecy and piece of our nation’s history,” said Stan Madison, the volunteer director at the restored Lyles Station Historic School and Museum. The school and museum, a few miles west of Princeton, preserves and shares the history of the Black pioneering settlement and many of its most esteemed residents.

“He tells the story,” Madison continued, “that the chestnut tree that Mr. Thomas Jefferson planted behind the White House was where all the major decisions in wartime were made. When you think about him being a part of that — just a servant — in the mix of something great, having moments with the president, the top officials, brigadier generals, and all. That has got to be the most heroic thing a person could be exposed to.”

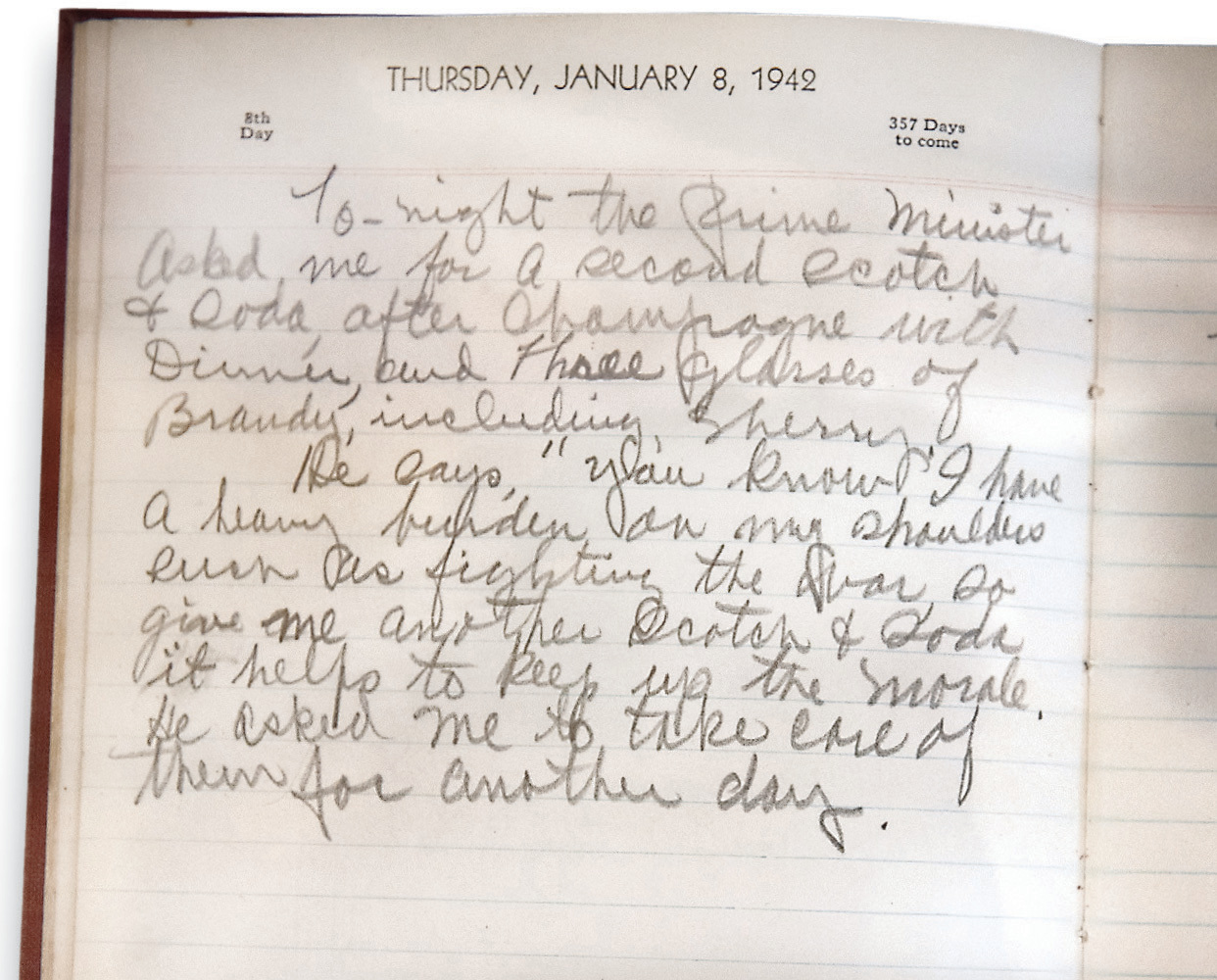

Fields detailed each day’s events in cryptic copious notes and journal entries during his years of service. While Fields’ observations centered on the minutiae of the menu and services, he often included comments and conversations he had and personal thoughts.

In 1960, seven years after leaving the White House, he began weaving together those journals and his recollections into a memoir of his 21 years there. Though restrained by today’s standards, his memoir provided a unique primary source insider’s view of daily life in the presidential household. And it provided his deeply personal account of American politics and world events from someone who was not a typical historian.

In 2000, James Still, playwright-in-residence for the Indiana Repertory Theatre at the time, began turning the memoir into a one-person play, “Looking Over the President’s Shoulder.” Premiering at the IRT in 2001, the play has been performed around the country and abroad. In June, Lyles Station and the Princeton Theatre are joining together to welcome Fields home for its 2024 Night at the Museum Live Event Series. They are bringing the play to Princeton for the museum’s Juneteenth commemoration.

MOVING ON

Lyles Station was a robust farming community in western Gibson County that was settled by Black families as far back as the time of Indiana’s statehood. When Fields was born, Lyles Station supported about 800 residents, a post office, a railroad station, an elementary school, two churches, two general stores, and a lumber mill. Fields’ father, Clinton, ran a general store and, on weekends, led the town’s brass band. In 1911, the family moved from Lyles Station to Indianapolis, where they operated a boarding house.

Fields developed a beautiful baritone and, initially, wanted to be an opera singer. In 1925, he left Indianapolis to enroll in Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music to pursue a teaching degree in music and a career as a singer.

While he had talent, he lacked tuition. An acquaintance helped him get an interview for a butler position for Samuel Stratton, the president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was hired on, and Stratton agreed to pay Fields’ tuition at the music conservatory. Fields quickly became a high-profile member of the MIT service staff.

A REMARKABLE OPPORTUNITY

While working for MIT, he met Thomas Edison, John D. Rockefeller, and many other dignitaries, including the wife of President Hoover, First Lady Lou Henry Hoover. But then, in October 1931, Stratton died unexpectedly, and Fields lost his means of support. Despite having a date set for his singing debut, Fields had to find work where it was available. By then, he had a wife, Edna, and a stepdaughter to support.

Hearing of Stratton’s death, the First Lady recalled the strapping butler who had waited on her during her visit to the Stratton household. She offered Fields a job as a butler in the White House. Realizing this was an opportunity he couldn’t afford to pass up, Fields and his family packed and moved to Washington, D.C. The position was only to be for a few months, and Fields had dreams of returning to the conservatory. But he was in a Catch-22: He couldn’t return to Boston without a job (and it was the Depression, after all); yet the longer he stayed in the White House, he feared, the less chance he’d ever return to following his dreams.

As it turned out, his “most thrilling experience” in his 21 years at the White House, he later recalled, was when he was invited to sing in the East Room for the Christmas Eve party given for the help staff in 1932. “I had my day,” he later wrote, “and a very appreciative audience gave me reason to believe they enjoyed my renditions.”

When the Roosevelts arrived in March 1933, Fields’ character and eye for detail quickly had him ascend to the head butler position and maître d’hôtel of the White House. He then planned and managed family, social, and state events at the White House, prepared menus, and directed the kitchen staff and more than a dozen butlers. He worked horrendous hours, 5:30 a.m. to 11 p.m., seven days a week, Madison noted. He met royalty, heads of state, military brass, and Hollywood stars.

“When you think about the importance of this guy,” Madison said, “he was considered part of that network that made things happen. He rolled the red carpet out; he found out what [the guests’] favorite ‘everything’ was; and when they got there to that door, I’m sure they were shocked to see a Black man open it to invite them into the White House.”

While in the White House, Fields brought his brother, George, on staff, as well. George Fields, who was born in Lyles Station in 1911, worked in the White House from 1937–1941. Once World War II began, he joined the Navy.

Alonzo Fields left the White House in February 1953 to attend to his wife whose health began failing. They moved back to Massachusetts. Over the next two decades, Edna would be in and out of the hospital. She died in West Medford, Massachusetts in 1973.

During that time, Fields found solace in writing his memoir from the extensive notes he had kept. “My 21 Years in the White House” made him something of a celebrity, and he began public speaking about his experiences. In the late 1970s, he became reacquainted with Mayland McLaughlin, also of West Medford, who had lost her spouse. An article published by the Medford Historical Society said the two had an “immediate connection,” and formed a deep bond. They married in 1980. Fields died of leukemia just short of his 94th birthday in March 1994 in Cambridge.

Though he heard negative comments like, “Who in the world would ever come from a hick town called ‘Lyles Station,’” Fields got to thinking about it, Madison said. That little community instilled in him a strong education and a strong character — a character which four U.S. presidents, their wives, other esteemed Americans, and foreign dignitaries must have found admirable. “My God. I’m pretty proud of where I came from,” Madison noted Fields might have said. “Starting out with an education in a small little farming community, and to say that that education took me all the way to the White House … I feel pretty blessed.”

Richard G. Biever is senior editor of Indiana Connection

Coming home

Fields’ life story to be performed in Princeton this summer

This June, Alonzo Fields, the Gibson County native who literally looked over the shoulders of four presidents as the chief butler at the White House, is coming home. Lyles Station Historic School and Museum and Princeton Theatre bring the award-winning play about Fields’ 21 years in the White House to Princeton.

Based on Fields’ memoir and the daily notes he kept, “Looking Over the President’s Shoulder” takes place on the eve of his last day on the job as maître d’hôtel at the White House. Throughout the one-man, two-act play, Fields reflects on his years of service to his country with humor and pride, including the presidential reactions to the attack on Pearl Harbor, the desegregation of the military, and the beginning of the Korean War.

Tickets are now on sale for the three performances at the Princeton Theatre, June 21–23. The Saturday performance on June 22 will be preceded by a special “Presidential Dinner.”

James Creer, a stage and voice-over actor and singer, will reprise the role of Fields in the play, which he has performed around the United States.

The play was originally commissioned by the Indiana Repertory Theatre in Indianapolis, where it premiered Nov. 2, 2001.

LOOKING OVER THE PRESIDENT’S SHOULDER

- Friday, June 21, 7 p.m.

- Saturday, June 22, 7 p.m. (with Presidential Dinner at 5:30 p.m.)

- Sunday, June 23, 2 p.m.

TICKETS

- Performance: $25

- Dinner and Performance: $90

THE PRINCETON THEATRE

301 W. Broadway St., Princeton, IN 47670

For more information, call 812-635-9185 or visit PrincetonTheatre.org.

Want to learn more about Lyles Station?

To learn more about Lyles Station, visit our profile here.