BACKGROUND PHOTO: Like swirling stars collected from the night sky, countless fireflies flicker across a field near a treeline. Lightning bugs, as they are also called, are perhaps the most “people pleasing” insect on earth: never a pest; always fascinating. The rural summer childhood ritual of collecting them in Ball jars at nightfall connects generations together like no other insect or animal. INSET ART: West Lafayette second grader Yangchen Yan adorned the cover of her jar-shaped booklet of firefly facts with these two fireflies. Yangchen is a student in Maggie Samudio’s second grade class at Cumberland Elementary. Samudio’s students for the past two years have been researching fireflies and lobbying the state Legislature to have the torch-bearing beetle adopted as the state insect.

How far would you go chasing a firefly?

Across town? Across the state? To the ends of the Earth?

In the cool of the evening this time of year, these little bioluminescent beetles emerge and begin beckoning both their mates and us with their tiny flashing greenish gold beacons. It’s easy to fall under their magical swirling spell.

But would your pursuit go so far as the one Kayla Xu, her teacher, class and school in West Lafayette have been on?

Kayla’s curiosity and quest to know why Indiana had no official “state insect” — and how it could capture one — took her entire second grade class at Cumberland Elementary cyber-tripping to nearby Purdue University. Entomologists there passed the torch they’d been carrying for the firefly to the kids. The chase to make the firefly the official state insect — with Purdue entomologists along for support — was now on.

Next, the pursuit wound its way through history — and from West Lafayette down the not-so-far-away banks of the Wabash (Indiana’s official “state song” and official “state river,” by the way) to New Harmony.

Next, the pursuit wound its way through history — and from West Lafayette down the not-so-far-away banks of the Wabash (Indiana’s official “state song” and official “state river,” by the way) to New Harmony.

Soon, state lawmakers joined in. They ran the firefly up the flagpole at the Indiana Statehouse, but still no luck. Yet, Kayla and her classmates insist the chase for the elusive state insect will continue on with new fervor. They hope a firefly fever will sweep the state, and their efforts will be supported statewide. The students are pinning their hopes on January’s General Assembly to make sure Indiana dawdles no more in selecting a state insect.

To paraphrase an old proverb: It’s not so much the destination of seeing the firefly made the state insect as much as it is the lessons learned along the way. “The whole experience is a journey,” said Maggie Samudio, Kayla’s second grade teacher.

The journey begins with a question or two

Not far into the fall semester of 2014, Samudio’s class was learning about the 50 states. Kayla had taken one of the books about states home to read more about all of them. Two days later, she came up to Samudio’s desk and told her teacher, “We have a problem.”

Kayla noticed some states had state musical instruments. “They had a state this, and a state that,” Samudio said. “She noticed the insects and said, ‘Indiana doesn’t have one. Why don’t we have one? How can we get one?’ And that’s how it all started.”

A firm believer in the “teachable moment,” Samudio promised Kayla she’d do some checking.

Indeed, 47 states have a designated state insect. Some have more than one. Indiana, Iowa and Michigan are the entomophobes.

“We don’t want to be the 50th in getting an insect,” added Kayla, who now just finished third grade in late May. “We’d stand out if we don’t have a state insect. It would be like — blaaaaank.”

Googling state insects, Samudio learned that Tom Turpin and other entomologists at Purdue University had suggested Indiana adopt the firefly as the state insect in the 1990s. More specifically, their firefly of choice was Pyractomena angulata, commonly called Say’s Firefly. This particular firefly was named after the famed naturalist Thomas Say, who discovered the species while researching insects near his home in New Harmony in the 1820s (please see sidebar).

“If it was good enough for Purdue and Tom Turpin,” said Samudio in going with the firefly, too, “it’s good enough for anybody and everybody.”

“I particularly thought the firefly was really good because I read this book, and it says fireflies are one of the most common insects,” added Kayla. “And in my mind, I say, ‘One of the most UN-gross insects.’”

“And that’s so important — to have an un-gross insect,” added Samudio. “We said ‘no stinkbugs.’ Right?”

“Right,” nodded Kayla and two other classmates from the previous year, Emma Williams and Vivi Agnew. The three girls helped carry the torch for the firefly. They rejoined Samudio in her classroom during lunch break last month to talk about the experiences from second grade and earlier this school year.

“They’re really fun,” Vivi added about fireflies. “They don’t harm you at all. It seems like they just want to be your friend.” And, she noted, “They can have an effect on anyone, any age.”

Vivi said people visiting Indiana from where there are no lightning bugs can be amazed seeing them for the first time. “It would be a like a sky of stars …”

“… Golden seeds sown about the night,” added Kayla, quoting Hoosier poet James Whitcomb Riley.

Emma said that everyone in the class was on board with the choice. “I think we all really admired the firefly when we found out about it,” she said. “Our teacher motivated us, and so we got to writing the letters and just trying to make a difference.”

Why a ‘state insect’?

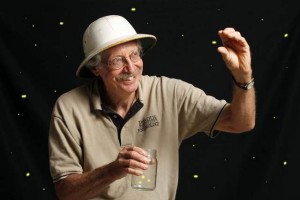

At the end of the spring semester last month, Tom Turpin reached into a desk drawer in his “bug-infested” office at Purdue and pulled out a tri-fold brochure, slightly discolored, from 20 years ago. “Support a state insect for Indiana,” the cover said, “The firefly.” It was one of the promotional materials they used.

“We were always looking for ways to keep entomology and insects in the public view,” said Turpin, who writes a monthly column called “On Six Legs” for Purdue’s Extension service and has come up with such popular events as the Bug Bowl and the State Fair’s cockroach races. “The idea was that if you have a state symbol, in this case a state insect, then this becomes something that multiplies by teachers using it in the classroom and by all those things where state symbols play a role.”

At that time, Turpin, colleague Arwin Provonsha and others gave a lot of thought to a variety of insects, including butterflies, but settled on the firefly. “Everybody sees the firefly and has positive feelings about it,” Turpin said. “When we were thinking about it originally, what would make a good state insect, none of us could come up with anything negative about the firefly.

“It’s not a pest on anything. It’s not the kind of thing that would sting you. It’s not the kind of thing that would bite you.” He said, “It is one of the few insects that can bind the generations together. Today, kids leave their iPads and whatever and go out and collect fireflies. Dad and Mom did it. Grandpa did it.”

In addition, the firefly seemingly offers lessons covering most all the disciplines of arts and sciences: the chemistry of its light, the flashing patterns of the mating rituals, the poetry and music it inspires and more.

That session of the General Assembly, a bill to make Say’s Firefly the state insect was introduced into the House and was passed. But, for some reason, Turpin said, the president pro tem of the Senate at the time “torpedoed” it. The House bill was ignored in the Senate and their attempt for a state insect sank.

A year or so later, they scuttled a second attempt when they learned a school near Lake Michigan was proposing an insect, the Karner blue. Once a common butterfly found along the Indiana Dunes, it had become almost extinct in Indiana. The Karner blue, too, and its supporters were soon shooed away by lawmakers.

While other groups have introduced other insects, including the Monarch butterfly, as potential state insects over the years, Turpin’s torch for the firefly remains steadfast. “My feeling is there is just a lot more going for fireflies in terms of the range, the number of people that participate with it in terms of capturing it and putting it in a jar, just lots of things that to me make it a better state symbol.”

Also, unlike some popular types of insects that have been adopted by multiple states, fireflies are the state insect for only two other states, Pennsylvania and Tennessee. Each of those states selected a more common type of firefly.

Turpin said over 40 kinds of fireflies have been found in Indiana, but Say’s Firefly is especially significant to the Hoosier state. “This is the only one we have in Indiana that was named by Thomas Say. So that was the connection. If we wanted it to be a state symbol: it’s here in Indiana; it was named by a well-known Indiana naturalist who really was considered the father of North American entomology by many people.”

State Rep. Sheila Klinker holds up a firefly finger puppet before the West Lafayette city council last month while speaking in support of students from the city’s Cumberland Elementary. The council was considering a resolution endorsing the students’ efforts to have Say’s Firefly adopted as the Indiana state insect and also making the firefly the official insect of West Lafayette. Klinker, whose District 27 includes Lafayette and portions of West Lafayette, cosponsored the students’ bill in the Indiana General Assembly in January. It failed to pass out of the natural resources committee. Undeterred, the students and their firefly supporters in the Statehouse are mounting another attempt for the 2017 General Assembly — and are hoping to gain statewide support from schools, city governments and other organizations and individuals. Looking on, from right, are Cumberland third graders Vivi Agnew, Kayla Xu and Emma Williams, and West Lafayette Mayor John R. Dennis. The council unanimously passed the resolution.

The firefly paper chase

Once Samudio’s class got to chasing Say’s Firefly, there was no going back.

In February 2015, the class did a persuasive writing project. Students wrote letters to top state elected officials in both Indianapolis and Washington, D.C., asking for guidance and support for their state insect idea. State Sen. Ron Alting, who represents much of Tippecanoe County, was the first to respond. While the deadline had passed to introduce bills for the 2015 session, Alting, a Republican, said he’d consider proposing a firefly bill for 2016.

In the meantime, Turpin visited Cumberland Elementary to teach the second graders more about fireflies. Also about that time, State Rep. Sheila Klinker, a Democrat whose district includes Lafayette and some of West Lafayette, visited the class and promised to draft a bill for the House. The students now had bipartisan support from the Republican and Democratic parties, and support in both chambers of the Statehouse.

When the most recent school year began in September of 2015, the students at Cumberland wrote more than 800 postcards and letters to Alting. Students at the school also worked to gather 700 signatures in support. In December, Alting visited the school, and announced he’d support their cause during a convocation.

Alting said the kids did their homework to show that Indiana was out of step with most of the country. Their arguments, he said, were hard to resist. “They are tougher than any lobbyist I know,” Alting told one reporter.

Samudio’s students this year made posters in support. One poster cleverly replaced the 19 stars on the Indiana flag with fireflies to remind legislators that a blue-dusky Indiana field of starry golden fireflies is the state flag come to life.

They created a Facebook page, www.facebook.com/firefly2016, and handed out white papers with 24 sound reasons why the firefly should be the state insect. The list included the arts and sciences fireflies inspire and the research based on their cool bioluminescent light, described as “the most efficient light in the world.”

For Indiana farmers, they noted that Turpin refers to fireflies as the “Paul Revere” of the insect world. When farmers see fireflies flashing, that’s a warning meaning conditions in the field are also right for rootworm larvae to start hatching and it’s time to check the crops.

They explained how the chemicals that make fireflies glow are being used in medical research for cancer and multiple sclerosis. And for the budget-minded Hoosiers, the students noted — in bold red ink — the state would benefit from “the taxes” collected from anticipated increased sales of firefly-themed merchandise.

In the House this past session, their bill received a hearing in the natural resources committee. An excited busload of students ventured to Indianapolis in January to testify before lawmakers and present their research. Unfortunately for the students, the insect issue was assigned to a House summer study committee. The Senate did not hear the bill at all.

“We’ve gotten a little bit farther than we thought we would,” said Samudio. “But we’re not where we want to be. We know it takes time. We were really truly hoping that once these legislators saw the kids, heard the kids, listened to the facts they researched, they were going to say ‘yes.’”

But state laws aren’t necessarily simple things to enact. Many — even ones that seem to have strong public backing — take years of hard work from supporters, multiple filings in the legislature, failures, grassroots building, haggling and redrafts before they gain enough support and are passed. And that’s a part of the civics lesson these students learned the hard way.

“It’s part of the process,” said Emma, “because it doesn’t just come to you easily. You have to struggle when you’re working hard for something. I don’t think it’s something that will get in our way or keep us from going.”

On their way

Some Hoosiers might look at all this and suggest the General Assembly has more serious matters before it to spend time and taxpayer dollars on than insects. But that might miss the bigger picture.

It may have started with a tiny insect, or rather, lack of one. But as Alting told the students in December: this is really about lessons in democracy.

This was the first opportunity for government to respond to a large group of spirited elementary kids to let them know that their government is working for them, too, he said. Their exercise in democracy let the students know that their state government was not far off and out of touch.

“We’re trying to teach these children to be responsible citizens and to treasure our democracy and use it properly. They’re learning how they can make changes,” said Samudio.

“They thought it was amazing that they can go speak to the people that represent them in our government,” she said of the trip to the Statehouse. “They know now if you have an idea, you can possibly have it put into a bill. But it has to go through a process.”

Kayla, Emma, Vivi and the rest of the Cumberland students haven’t given up on their quest for the firefly. In fact, they now sound more determined, a little older (as soon-to-be fourth graders!) and wiser. They said they realize they need to expand their efforts statewide.

They already have plans to take their curiosity of the torch-bearing beetles to the ends of the Earth and beyond. From their study about how fireflies light up, using luciferin and luciferase mixed with oxygen, and studies of how liquids react with one another in zero gravity a question arose: Could fireflies light up in space?

Samudio asked Steven Collicott from Purdue’s School of Aeronautics and Astronautics. That led to a collaboration between the second graders and Collicott’s Purdue students studying zero gravity. Instead of answering the question for the students, Collicott also seized on the teachable moment and contacted the Arete-STEM Foundation, an organization established by a retired elementary school teacher to enable schools to launch payloads onboard commercial rockets for about $3,000.

The experiment, “Zero Gravity Glow Experiment” or ZGGE, was approved and is scheduled to launch this fall. The mission patch includes a firefly and the initials CP for Cumberland/Purdue.

Because real fireflies cannot be sent to space, the experiment will replicate the firefly chemistry in space. The payload for each research experiment is confined to a four-inch cube. Six Purdue aerospace engineering undergrads are guiding the second graders through the experiment design process. This spring, during a visit to their classroom, the Purdue students designing the aluminum container for the experiment had the second graders autograph the container which will be used.

A signal from the spacecraft’s computer system will trigger the luciferin and luciferase to mix once the rocket reaches sub-orbital space. A tiny camera inside the cube will record the experiment and return to Earth with video answering the students’ question: did the chemicals glow?

“I think this experiment that’s going into space might give us more of a chance to have our state insect the firefly because I think more people will hear about it,” said Emma, who, already sounding like an experienced lobbyist, realized the political hay that could be made from such light.

The lawmakers who supported them last session have pledged their support again next year. Meanwhile, they picked up the support of the West Lafayette city council. In a resolution passed May 2, the council adopted Say’s Firefly as the city insect and urged the Indiana General Assembly to do the same for the state.

The trio said they hope other cities and counties will pass similar resolutions. And they asked that average citizens who share a common delight for the firefly contact their legislators across the state to ask for support for the firefly in the next General Assembly.

“It’s going to take many Hoosier voices to take this to the finish line,” said their teacher.

And as they’ve now learned, “Everyone has a voice,” said Emma.

Richard G. Biever is senior editor of Electric Consumer.

Be sure to check out these related stories:

- When it comes to an insect, Indiana draws a ‘blaaaaaaank’

- Proposed insect named for famed New Harmony naturalist

- Oh, Say, can you see if it’s a Say’s Firefly?

- Harnessing the power of the lightning bug

- This firefly shines light on safety

- Waxing poetic in the firefly’s glow

- Create your own mascot; maybe win a plush Louie the Lightning Bug!

Be sure to check out these websites for more information about fireflies: