By Patrick Keegan and Amy Wheeless

I’m considering replacing my current heating system with a geothermal heat pump. It is comparatively pricey to other options. Would a geothermal heat pump be a good choice for me?

I’m considering replacing my current heating system with a geothermal heat pump. It is comparatively pricey to other options. Would a geothermal heat pump be a good choice for me?

Heating and cooling account for a large percentage of overall home energy use, so upgrading to a more efficient system is a great way to reduce your energy bill. A geothermal heat pump, also known as a ground source heat pump, is among the most efficient systems.

Even when it is extremely hot or cold outside, the temperature a few feet below the surface of the ground remains relatively constant and moderate. A geothermal heat pump system uses this constant ground temperature to help heat and cool your home.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says geothermal heat pumps use up to 44 percent less energy than traditional air-source heat pumps, and up to 72 percent less energy than electric resistance heaters combined with standard air conditioners.

A geothermal heat pump system is made up of three main components:

• The collector, or loop field, which is in the ground and cycles an antifreeze-like liquid, through dense plastic tubing;

• The heat pump that is in your home;

• The duct system that distributes the heated or cooled air throughout your home.

During the winter, the collector absorbs the heat stored in the ground and the liquid carries that heat to the heat pump, which concentrates it and blows it into the duct work, warming your home. In the summer, the heat pump extracts heat from the home and transfers it to the cooler ground. Also, the heat pulled from your home in summer can be used to help heat your home’s water for more savings.

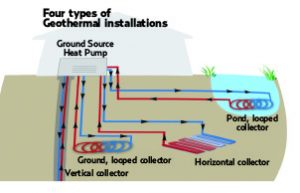

The collector that exchanges heating and cooling with the ground can be set up in one of four main ways:

• Horizontal system: Plastic tubing is placed in trenches 4 to 6 feet below the surface of the ground. This system works well when a home or business has sufficient available land, as these systems may require up to 400 feet of trenches to be dug, especially if it’s a new construction.

• Vertical system: If the site does not have sufficient space for a horizontal system, a collector can be placed vertically. In this system, a drill digs 100 to 400 feet below the surface and places the tubing. This system can be more costly than a horizontal system, but will have less impact on any existing landscaping and can be used on smaller lots.

• Pond system: If a home has access to a pond or lake, a pond system (also known as a water source heat pump) may be possible. The loop field is connected to the heat pump and then placed at least eight feet below the surface of the water. If a homeowner has access to a pond that is sufficiently wide and deep, this option can be the lowest cost.

• Horizontal Bore system: uses plastic tubing placed in holes that are bored horizontally 15 feet below the surface of the ground. This system works well when an existing home or business has sufficient available land, as these systems may require up to 600 feet of holes to be bored. This type of loop can be placed under driveways, septic systems and existing buildings.

Geothermal systems typically cost more than other heating systems, largely because of the collector and the associated digging or drilling, but their high efficiency can help reduce the payback time. The cost will vary based on whether new ductwork is needed and the type of collector you install, among other factors. However, there are incentives available for those who install qualified geothermal heat pumps. Most notably, there is a 30 percent federal tax credit for installing an ENERGY STAR-rated system, or replacing an older unit, before the end of 2016. Indiana offers a state property tax deduction for the installation of geothermal technologies, and your electric co-op may offer rebates.

Those building new homes should consider geothermal at the outset — when the system can be included in the mortgage.

Talk with your local co-op’s energy advisor who can help you evaluate the different heating and cooling options that would be best for your home.

Patrick Keegan writes on consumer and cooperative affairs for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, service arm of the nation’s 900-plus consumer-owned, not-for-profit electric cooperatives based in Arlington, Virginia. Amy Wheeless writes for Collaborative Efficiency. For more information, visit:www.collaborativeefficiency.com/energytips or email Pat Keegan at energytips@collaborativeefficiency.com.