Rowena Richardson remembers long summer days as a kid in Monument City. She and playmates “lived” in the cool shade of the grassy playground behind the big red brick school building. They’d play on the wooden-seated swings, and sometimes get really adventurous. “The school had one of those big old round fire escapes that went all the way to the third floor,” she said. “Us kids would go down that till they’d catch us and run us off. And we’d try again the next day.”

Nancy Smith remembers her wedding day in 1954 at Monument City’s Wesleyan Church. She and her husband, Larry, filled the white clapboard structure that Sunday with relatives who had come in for their celebration — and for Christmas the day before. She said Dec. 26, her wedding day, was so unseasonably mild — nearly 60 degrees — she would not have needed the new winter coat she wanted but hadn’t had time to get before the big occasion.

Don Schenkel told his wife and daughter as they walked south toward the Salamonie Lake that the last time he traveled that same road was probably 50 years ago. He remembers coming down to Monument City while visiting his aunt and uncle who lived north of town. He and his cousins would sometimes camp along the Salamonie River along the south edge of town. “There was a church, a store and a few houses and the old school. That was about it,” he said.

A hand-colored aerial photo shows Monument City prior to 1964, looking from east to west (bottom to top) and south to north (left to right). The Salamonie River is on the far left. The red school building, white Wesleyan Church and cemetery are at top right.

Town photos courtesy of Rowena Richardson.

That was about all there was to Monument City … a church, a school, a few houses … when it was bulldozed in 1964 to make way for the building of the dam down stream on the Salamonie and the rising waters of the new reservoir that would soon be above it. That was about all there ever was to the town. That … and the lives, and times, and memories of all the people who called Monument City “home.”

It would be impossible to count and recount all the memories folks shared during a kind of impromptu Monument City “homecoming” on two Sunday evenings, July 29 and Aug. 5. The Indiana Department of Natural Resources hosted the supervised tours to the town site to satisfy a surprising, sudden, large public curiosity in the former town after its remains were exposed by the receding Salamonie reservoir. Water levels at lakes around the state are lower because of the drought.

Initially, inaccurate news accounts said this summer’s historic drought had revealed Monument City for the “first time” in 50 years. Those reports led to even more exaggerated tales said Teresa Rody, interpretive naturalist at the Upper Wabash Interpretive Services. “A media outlet said it was like ‘Atlantis rising from the water.’ It gave people the feeling that they could go there and see houses standing.”

Initially, inaccurate news accounts said this summer’s historic drought had revealed Monument City for the “first time” in 50 years. Those reports led to even more exaggerated tales said Teresa Rody, interpretive naturalist at the Upper Wabash Interpretive Services. “A media outlet said it was like ‘Atlantis rising from the water.’ It gave people the feeling that they could go there and see houses standing.”

The reservoir level, controlled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Louisville, was down this summer by some 14 feet from its normal “summer pool” because of the dry conditions. Beaches at the state recreation sites, operated by the DNR, have been closed at Salamonie and its sister reservoir, Mississinewa, which straddles neighboring Wabash and Miami counties.

But the reality is the remains of Monument City — physically only a few stone foundations, a scattering of bricks, gravel roadbeds, slabs of concrete and such — are exposed each fall and winter. That’s when the reservoir is drawn down to its winter pool, about 25 feet below the normal summer level. This is done so the reservoir can absorb and retain the usual increased runoff of rain and snowmelt that would flood the Salamonie and Wabash rivers each late winter and spring.

But the reality is the remains of Monument City — physically only a few stone foundations, a scattering of bricks, gravel roadbeds, slabs of concrete and such — are exposed each fall and winter. That’s when the reservoir is drawn down to its winter pool, about 25 feet below the normal summer level. This is done so the reservoir can absorb and retain the usual increased runoff of rain and snowmelt that would flood the Salamonie and Wabash rivers each late winter and spring.

The winter pool is about another 10 feet lower than this summer’s receded level. (Internet users can zoom in on Google satellite images of Salamonie and see the old roads and foundations.)

Phil Bloom, director of communications with the DNR, said the department considered the exposure of the remains a “non-story” since they reappear each fall. But after stories first appeared, which were then picked up and circulated nationally by the likes of USA Today and the Weather Channel, “It got a life of its own,” he said.

As if on a pilgrimage, visitors make their way to and from what once was Monument City on the edge of the Salamonie reservoir Aug. 5. Though exposed in winter, the old town site and this portion of road are usually under water in summer. The Indiana Department of Natural Resources hosted two Sunday evening “homecomings” at the site in response to public interest after it became exposed by the drought-lowered lake.

By mid-July, people started coming to the site not just to look around. Some brought shovels to scavenge for artifacts, Bloom said. That’s when the DNR closed the site. State and federal laws protect all potential artifacts at the site, though few, if any, are there. When calls persisted about Monument City, the DNR decided to reopen the site for the limited two evenings of supervised touring.

That first Sunday, an estimated 850-1,000 curious sightseers and former residents took advantage of the program to visit the parched and weedy shoreline. About another 800 came for the second.

The tours met at the Interpretive Center in Salamonie’s Lost Bridge West Recreation Area. Rody briefed groups about Monument City, the site and the reservoirs. Visitors were encouraged to check out displays of photos and a large three-dimensional map of the reservoir which shows where Monument City was and summer and winter pools. Then folks caravaned the short distance up Ind. 105, over the original river channel, then east to Huntington County Road 800 West. There, they parked along the roadside next to cornfields and either walked the half mile or more south downhill to the water’s edge or were shuttled down in a van by DNR staff.

DNR staff members weren’t the only ones surprised by the turnout.

“We sat down for dinner and looked out the window and thought, ‘Oh, my. Why are there 15 people in front of our house?’” said Kristy Hamblen, who lives in one of the last homes on the road before it dead ends in the lake. “Then we walked out the door, and there were people all the way down to 105.”

She and her husband, Randall, United REMC consumers, have a catering business and wasted no time serving the soft drinks and water they had on hand. The next week, he was prepared with pans of his family-recipe Southern brisket. They sold sandwiches and chips to the masses moving by their yard on the normally quiet country road.

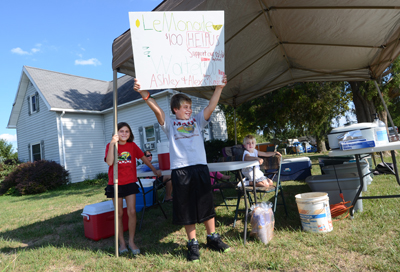

Neighbor Jill Ware and her three children — Alex, Ashley and Andrew — also saw entrepreneur opportunities in the passersby. They set up a lemonade stand to raise money for their 4-H rabbit projects. But they were too far off the beaten path, down an intersecting side road, to attract customers. “It’s all about location,” Ware quipped.

Neighbor Jill Ware and her three children — Alex, Ashley and Andrew — also saw entrepreneur opportunities in the passersby. They set up a lemonade stand to raise money for their 4-H rabbit projects. But they were too far off the beaten path, down an intersecting side road, to attract customers. “It’s all about location,” Ware quipped.

That’s when the Hamblens invited them to join their stand under a canopy along the main road.

Ware said she often had taken her children down the dead end road to the reservoir to study geology and wildlife. After daughter Ashley asked why all those people were going there, the 9-year-old noted, “We’ve been going there all the time — and now it’s famous.”

A monument to a city

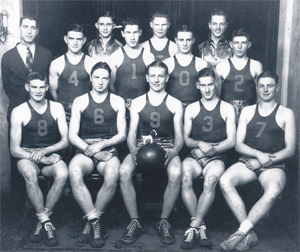

Luann Moberg, left, pays homage to her dad, Jack L. Miller, number 3 in the 1939 team photo, by posing in his Monument City High School varsity letterman’s sweater while taking the tour. Moberg grew up in nearby Wabash. Her dad died in 2009.

The first stop on the walk to Monument City was across the road and just south of the Hamblens’ home. The Monument City Cemetery, about a mile north of the river channel, is where the graves and headstones from the cemetery at the Wesleyan Church were moved as the town was dismantled. Also at the cemetery entrance is the obelisk-shaped monument, topped by a spread-winged eagle, that gave Monument City its name.

The monument was erected in 1869 by folks in Huntington County’s Polk Township to honor the 27 local men who were killed or fatally wounded in the Civil War. The monument was placed at a crossroads near the center of the township – what became roads 800 W and 350 S — just north of the Salamonie River. In 1876, the town was platted at those crossroads and took the name Monument City because of the landmark.

Devastating floods along the Wabash River over the following decades led to control efforts. In 1958, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was authorized to build a series of flood control dams on the upper Wabash and two of its tributaries, the Salamonie and the Mississinewa. The dams would protect larger cities like Huntington, Wabash, Peru, Logansport, Lafayette and others farther down the Wabash and beyond. Three small towns would be sacrificed: Monument City was the largest; Dora and Somerset would also be swallowed by the projects. Part of the town of Mount Etna was also taken.

Devastating floods along the Wabash River over the following decades led to control efforts. In 1958, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was authorized to build a series of flood control dams on the upper Wabash and two of its tributaries, the Salamonie and the Mississinewa. The dams would protect larger cities like Huntington, Wabash, Peru, Logansport, Lafayette and others farther down the Wabash and beyond. Three small towns would be sacrificed: Monument City was the largest; Dora and Somerset would also be swallowed by the projects. Part of the town of Mount Etna was also taken.

Monument City was abandoned in 1964. A few of the homes were moved, but most were bulldozed and hauled away. Most of its two dozen residents moved into the nearby countryside. The dam was completed in 1967. By the winter of 1967, the reservoir began flooding the valley.

The $60 million project has averted an estimated $325 billion in flood damage, according to the corps of engineers. The corps also estimates that Salamonie’s recreational byproduct brings in some $17.4 million annually to the local economy.

“I’ve seen the good things the reservoir has achieved,” noted Rowena Richardson, who was 11 years old when she, two older siblings and their parents were forced to move. “It was good for humanity, bad for the families.”

Visitors during the second of two special tours to the site of the former Monument City wander around the foundation and bricks of the school (inset) which re-emerged along the shore of Salamonie Lake this summer. The drought lowered the water level at the reservoir exposing the old town’s remains.

Her family was one of the few that moved their house to higher ground east of town. They jacked up the house and put wheels beneath it. “My sister, Roma, me and cousin Terry were riding in the house as it was being moved,” she recalled.

Just east of town, where the pavement changed to gravel, the house jackknifed and slipped into a large ditch. “Fortunately, the trees lining the road caught it from being tipped on its side,” Richardson noted. “However, all the dishes came out of the cupboards, the 9-year-old goldfish went flying and Puff [their white cat trapped in a bedroom by furniture] suffered PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] and was never right after that!”

She said the house survived with just some cracked plaster and dented eaves, but her dad immediately sold it to the moving company. The house ended up at its intended location, while her family built a new one next door.

But living in the country wasn’t like living near the old schoolyard. Playmates were scarce. She said she missed the close-knit community they called home. “As a kid, it was very sad to see your home taken from you that you couldn’t go back to … You can’t go back home — when it’s under water.”

Memories

The tours gave folks a chance to visit the site while the weather was warm, dry and sunny. In winter, when it is exposed, visitors can expect cold, mud and wind for the half-mile walk from where a gate crosses the dead end road to the site.

The Salamonie Interpretive Center offers a 3D map of the reservoir. Looking over the Monument City site (the gray area with the red light) is Nancy Smith who was married in Monument City 58 years ago. With her are her daughter, Anita Hughes, and grandsons, from left, Maxwell, Jackson and Alex.

Nancy Smith came with her daughter, Anita Hughes, and grandchildren for the tour. Hughes said her husband grew up just up the road. “When the water would be real low, he’d go down and wander around in the basements and the foundations,” she said he told her. “It’s kind of nice for the kids to see where their dad played, and neat for grandma to show us where she was married,” she added. “They haven’t ever gotten to see this.”

Richardson had been back to the site last spring mushroom hunting. That was the first time she’d been there in several years.

She and her older siblings used to visit their old homesite in the winter and reminisce, but once the road was gated, the walk became too much. Like so many former residents, they slowly stopped coming.

Richardson, a United REMC consumer, brought an album with old photos to the second of the tours. As a historical re-enactor, the 59-year-old has a keen love of history and felt compelled to be there. She stood on the remains of the road that ran in front of her childhood home. From where she used to sit and pop tar bubbles on hot afternoons, she greeted sightseers, showed photos, answered questions and shared history.

Rowena Richardson, left, shares photos and stories from Monument City’s past with those touring the site of the former town. Richardson, who lived there till she was 11 when the reservoir was built, greeted folks from her old homesite.

“Most folks didn’t really understand what was there, what they were looking at,” she said later. “I wanted to share the stories with folks that didn’t know.”

As she stood there sharing memories — just a stone’s throw from where the namesake monument stood — she noted, “It doesn’t make sense to just look at the foundations. To see the pictures makes you understand that people lived here.”

“The true story here is in the lives and stories of former residents of the Salamonie area,” noted Marvin McNew, director of the Upper Wabash interpretive services. “We’re hoping to connect once again with former residents of Monument City and other reservoir locations. There are so many stories … and fond memories of days past that we would like to record … and share with future generations.”

As curious visitors who ventured to the Monument City site on those two Sundays learned, the only things left of the town are the relocated monument and graves, some original bricks, foundations and flooring — and the memories of a place that time and water have not erased.

At the close of the second Sunday of evening tours to the old Monument City site on the Salamonie Lake shoreline, Darla Williams of Bryan, Ohio, takes a photo of the town’s namesake. The monument, erected in 1869, remembers 27 soldiers from Huntington County’s Polk Township who died in the Civil War. It, along with the town’s graves, were moved to a new cemetery a mile north of the town when the reservoir was created in the mid-1960s.

Story and photos by Richard G. Biever, senior editor.

Former residents are encouraged to share memories Oct. 20 at the Salamonie Interpretive Center. Please call 260-468-2127 to set up a time.

For more information about Salamonie Lake, please visit these websites:

• http://www.in.gov/dnr/parklake/2952.htm