By Richard G. Biever

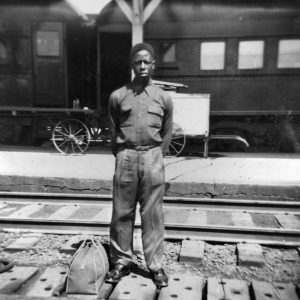

On or about April 8, 1952, an 18-year-old baseball player with an unusual swing packed a small travel bag for his first road trip. He hugged his weeping mother; waved goodbye to his dad, siblings, and coach at the train station; and was off to join his first professional team for spring training.

The team was the Indianapolis Clowns, reigning champs of the Negro American League.

The ballplayer was Henry Aaron.

Over the next quarter century, Aaron’s basepaths took him from the Clowns to big league teams in Milwaukee and Atlanta, and ultimately to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Along the way, he transcended baseball. Aaron became an important and revered figure across all of American culture.

When his playing days were done, he continued leading as a baseball executive and a champion for racial equality and social justice.

Aaron died Jan. 22, 2021, at the age of 86, joining a whole lineup of fellow Hall of Famers from his era who died during the pandemic.

In a memorial tribute, Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, said, “I am tremendously honored and humbled to reflect on where his illustrious professional baseball career began — the Negro leagues.”

While Aaron’s stint — 26 games — in the Negro leagues was brief, Hoosiers can take a smidgeon of shirttail pride: it was with the Indianapolis Clowns that he perfected his swing, gained his confidence and was shown the way.

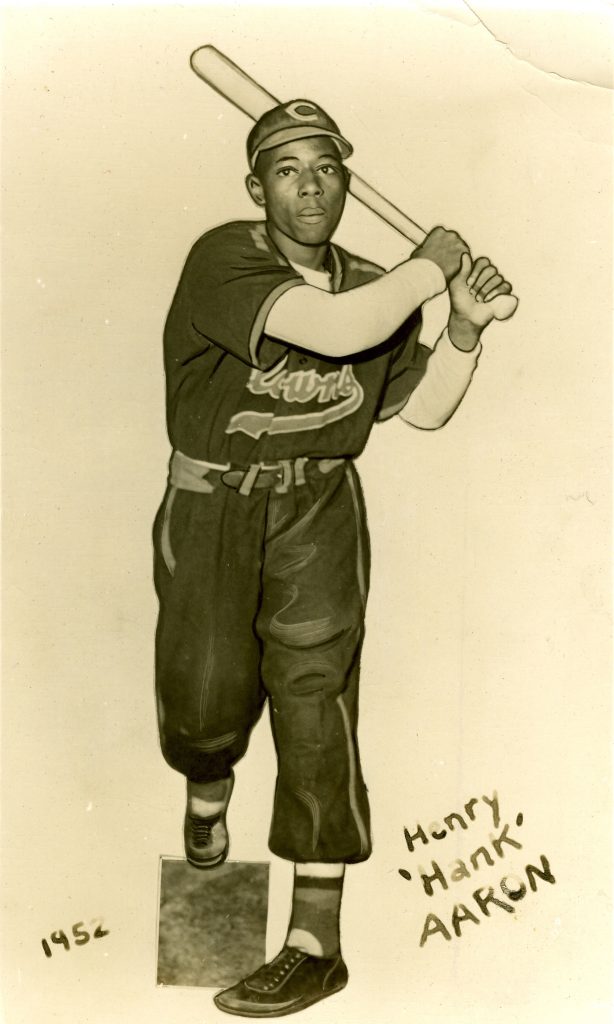

Before joining the Clowns, Aaron held the bat incorrectly — with the left hand above the right — opposite of how a right-handed hitter is supposed to grip the bat.

“The fear is that you would break your wrists hitting in that manner,” Kendrick noted. “Well, Henry Aaron is knocking the cover off the ball in a highly unorthodox fashion. When he gets to the Clowns, they put the right hand on top, and the rest is history.”

Sending in the Clowns

The Indianapolis Clowns were among the most storied and successful teams of the Negro leagues. The Clowns mixed showmanship and skill — baseball’s version of the Harlem Globetrotters. Though officially hailing from Indianapolis, the Clowns played only several games a season in Indy. Most of the time, they barnstormed throughout the South, Midwest, and East.

The Clowns and other Negro teams formed after Black and Hispanic players were shut out from major league baseball around 1900 by racism. Their first successful league organized in Kansas City in 1920. For almost 30 years, the Negro leagues fielded the likes of Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and Indianapolis native Oscar Charleston, ballplayers considered among the greatest ever — period.

Major league baseball finally integrated in 1947 with Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers — 75 years ago this spring. That key moment for baseball and civil rights spelled the beginning of the end for the Negro leagues. The best Black players began joining major league teams, and Black fans followed them.

Originally based in Florida, the Clowns added comedy to bolster attendance during the Depression. The clowning schtick brought fans through the turnstiles; their winning play in the field kept fans coming back.

In the early 1940s, Syd Pollock, the upstate New York impresario who owned the Clowns, moved the team to Cincinnati to gain a broader audience in the North. In 1944, the Clowns split their “home” between Cincinnati and Indianapolis. Finally, in 1946, Indianapolis became the official home.

Not everyone was amused with some of the Clowns’ antics that played up racial stereotypes. The Pittsburgh Courier, a leading Black newspaper of the day, rebuked Pollock in a 1944 column saying the Clowns “have done little of significance to uplift the prestige of Negro baseball.” The Homestead Grays, a long-standing Negro National League team just east of Pittsburgh, found the Clowns’ burlesque “show boat” so objectionable they refused to play them.

By the time Aaron joined the Clowns, they were focused more on the horsehide than horsing around, but the Negro leagues were in decline. Though only six of the 16 big league teams had broken the color line, teams and even the Negro National League had folded.

The remaining teams survived by signing talented Black players, then selling their contracts to major league teams. Coming off the 1951 championship, the Clowns sold two of its best players to the Boston Braves.

In Aaron’s hometown of Mobile, Alabama, Ed Scott, a former Clowns player, acted as a scout for Pollock while managing a semi-pro team. He recruited a 16-year-old Aaron when he saw him playing softball. In the summer of 1951, Scott called Pollock praising his 5-foot-6, 150-pound prospect. He noted Aaron could “rip the hide off a baseball …. like few I’ve ever seen.”

That November, the Clowns signed Aaron to a contract for $200 a month for the spring of 1952. Coincidentally, the Clowns were the first professional team Aaron ever saw play when they had come through Mobile in 1948.

In his autobiography, “I Had a Hammer,” Aaron wrote, “I felt in my bones that someday I would join Jackie Robinson, and here was my chance.”

Suiting up

Upon arriving at the Clowns spring training in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, April 10, 1952, Aaron felt unwelcomed by the veterans at first and apprehensive about even making the team. “They made fun of my worn-out shoes, and they asked me if I got my glove from the Salvation Army,” he wrote.

Every time he stepped into the batting cage, one would charge in telling him to get out. If not for an injury to a regular infielder, Aaron said he might have been on his way back to Mobile to finish high school.

“As soon as I got to the plate,” Aaron noted, “the hits started to fall. I got one-hop singles through the infield, low-riding doubles through the outfield, and a home run to right-center now and then.”

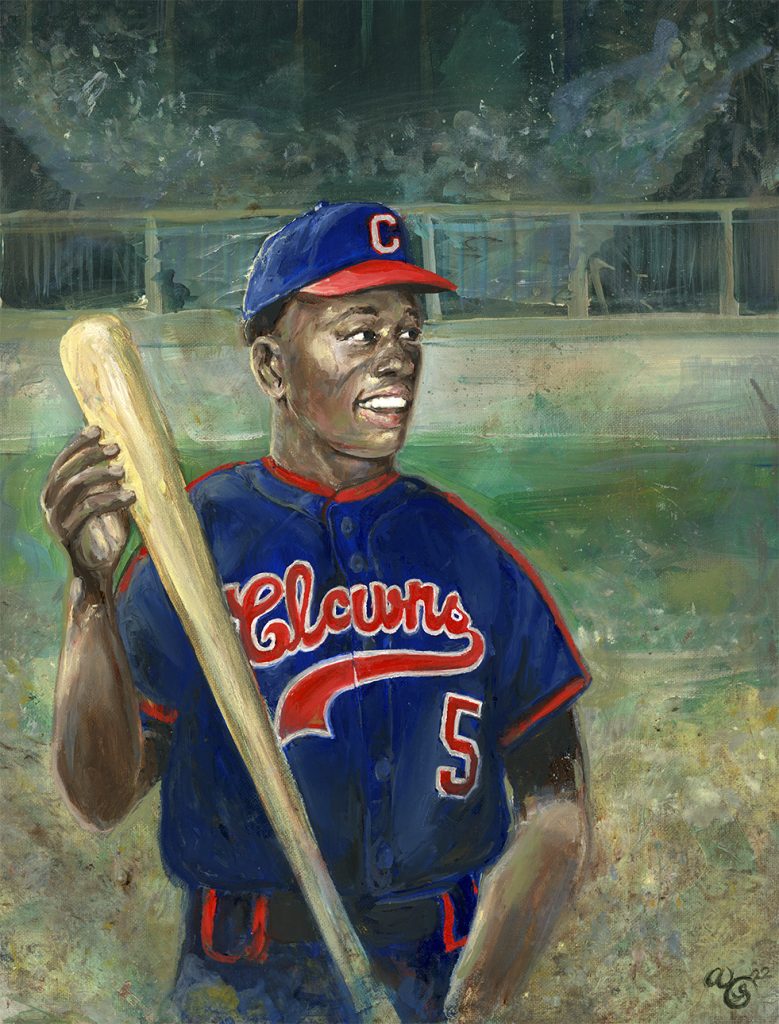

Suiting up in Indy’s blue and red flannels was unforgettable, Aaron later wrote. “When I walked out on the field for my first game wearing a Clowns uniform, I felt like I was something special.”

The Clowns’ schedule took them barnstorming through the South to Oklahoma, turning around, going back through the South, and then heading up the East Coast.

As the miles and hits piled up, the rookie phenom earned both the respect of his teammates and his first nickname — “Pork Chops.” “The man ate pork chops three meals a day, two for breakfast, two for lunch, three for dinner …,” pitcher Frank Carswell told Alan Pollock for his biography about his father Syd. “Had players thinking about strict pork chop diets so’s they could hit like he could.”

When a little girl asked Aaron why he was called Pork Chops at a visit to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in 1999, he replied with a smile, “Because that was the only thing I knew to order off the menu.”

At some point along the road, Aaron flipped his hands on the bat. Various versions from various sources vaguely note when and how. One account was that Clowns manager Buster Haywood changed his grip — reluctantly — not wanting to tinker with Aaron’s swing. Another was that it was Pollock. Another source said a scout for the Braves, giving Aaron a looksee in Buffalo, suggested the change.

Scott, Aaron’s manager in Mobile, told writer Howard Bryant in his 2010 Aaron biography that he never saw Aaron bat cross-handed — and certainly would have noticed if he had. “I’m telling you, I never saw it,” Scott said, “but that became part of the legend. No point arguing about it now.”

While Aaron was tearing up the league, Pollock sent letters to every major league team trying to get Aaron scouted and signed to a major league contract. After the Braves scouted Aaron in Buffalo in late May, they made a deal: $10,000 to the Clowns for Aaron’s contract; a salary of $350 a month for Aaron. The New York Giants also offered a deal giving the Clowns $5,000 more for the contract but paying Aaron $100 less a month. Pollock recommended he sign with the Braves — which he did. Aaron was to report to the Braves’ farm club, the Bears in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, June 11.

Meanwhile, the Clowns were making their first trip of the season to Indianapolis June 10 — a double header against the Chicago American Giants. The Indianapolis Recorder, the weekly Black community newspaper, noted Aaron’s signing by the Braves and that this would be the only chance to catch the rising star in Indianapolis. No record can be found if Aaron played, but the Recorder briefly mentioned in its next issue the Clowns lost both games.

Despite being in first place, the Clowns drew little coverage by Indianapolis newspapers in 1952. The Indianapolis Indians, the minor league team of the Cleveland Indians, had integrated that spring and overshadowed the Clowns.

Aaron later said he never played a home game with the Clowns. “I only saw Indianapolis through the window of a bus,” he told Paul Debono who wrote a book on another Indianapolis Negro team, the ABCs. “We played all our games on the road.”

In his 26 games with the Clowns, Aaron batted .366 and hit five home runs. For the remainder of the 1952 season, Aaron hit .336 for the Bears and was named the Northern League’s “Rookie of the Year.”

After the minor league season ended, Aaron rejoined the Clowns for the Negro American League championship. The Clowns had won the first half of the season, when Aaron was on the team, and the Birmingham Black Barons won the second half. To determine the champion, the two would play a best-of-13 series across several cities in the South. The games started in Birmingham and wrapped up in New Orleans.

The Black Barons took a five-to-three game lead over the Clowns. But the Clowns rallied for four straight wins to take the series seven games to five.

The Indianapolis Recorder summarized the series in a short Oct. 18 article that read in part: “Henry Aaron, the shortstop who was sold to the Boston Braves earlier this season, played with the Clowns and was the hitting star of the series. He batted .402 and slammed out five homers.”

Just two seasons removed from his barnstorming with the Clowns, Aaron made his major league debut in 1954 with the Braves, who had just moved to Milwaukee. He played 21 seasons for the Braves in Milwaukee, then Atlanta.

Coming home

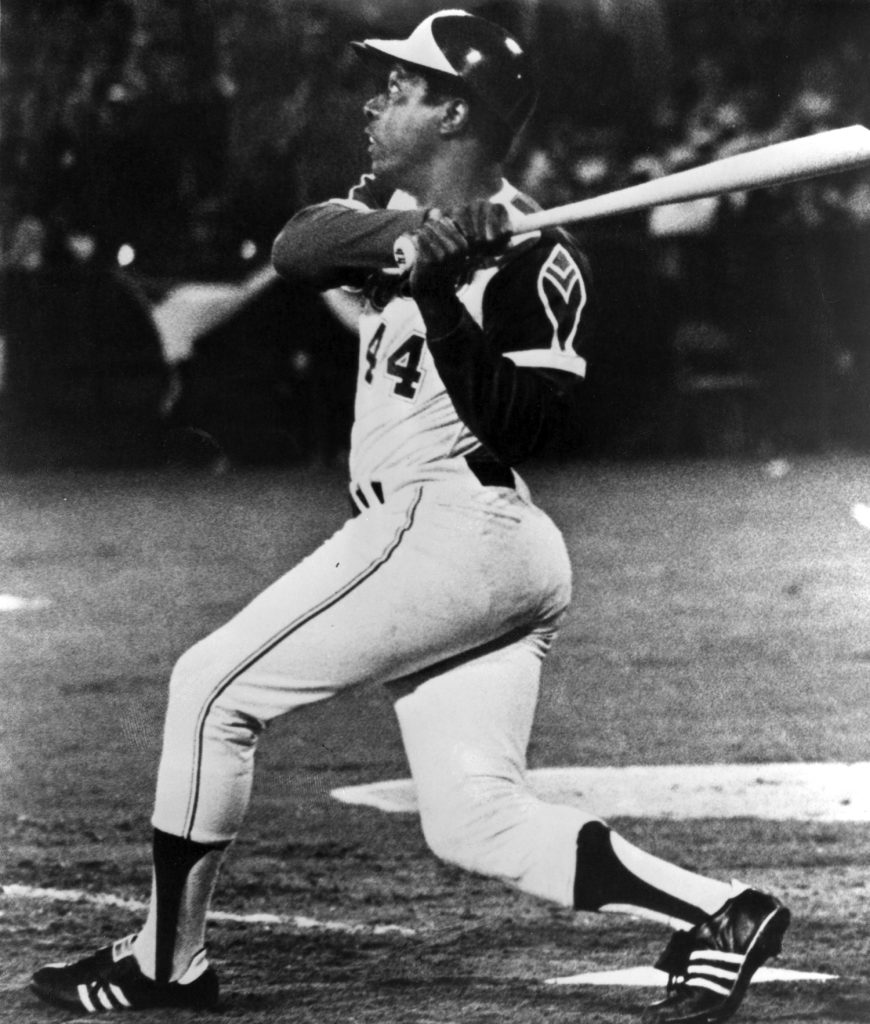

The opening of Aaron’s autobiography describes that April day in 1952 when he first left home for spring training with the Clowns. But his most celebrated “homecoming” came 22 years to the day later, April 8, 1974, in Atlanta. That was the night the world saw Aaron hit career home run 715 to break Babe Ruth’s longstanding record.

After the 1974 season, Aaron was traded to the Milwaukee Brewers, letting him finish his big league career in the city where it started. Aaron retired at the end of the 1976 season and was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, his first year of eligibility.

Writing in the foreword of a book about Negro league players in August 2020, just five months before he died, Aaron reflected with gratitude toward both the Clowns and providence for the career path he traveled.

“If it hadn’t been for the Indianapolis Clowns offering me a chance to play, I don’t know what would have happened to me…. Those months I spent on the Clowns helped me tremendously — not only teaching me how to play the game itself but also showing me that I belonged at that level.”

He wrote, “God had put His hands on me. He had showed me the direction…. God showed me the way.”

RICHARD G. BIEVER is senior editor of Indiana Connection.

Aaron remembered in bobbleheads

To celebrate Hank Aaron’s first professional baseball with the Indianapolis Clowns and commemorate his passing in 2021, two bobbleheads featuring Aaron in his blue No. 5 Clowns uniform have been released this spring. The first bobblehead features Aaron batting cross-handed, as he did when he joined the Clowns, while the second features Aaron kneeling with four bats.

The bobbleheads are available for purchase through the National Bobblehead Hall of Fame and Museum’s Online Store (www.BobbleheadHall.com). The bobbleheads are $30 each plus $8 for shipping.

For more info

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

1616 E. 18th St., Kansas City, MO

www.nlbm.com

The National Bobblehead Hall of Fame and Museum

170 S. 1st St., Milwaukee, WI

BobbleheadHall.com

Dreams Fulfilled was organized to promote the Negro National League Centennial in 2020 and is dedicated to promoting the history of the

Negro leagues.

NegroLeaguesHistory.com