By Brian D. Smith

Ernie Pyle was an embedded reporter more than a half-century before anyone ever heard the term, sending regular dispatches from the European, North African, and Pacific battlefronts of World War II. The Dana, Indiana, native witnessed the firebombing of London, wandered Omaha Beach at Normandy on the morning after D-Day, and shared in the revelry of a liberated Paris. He ate, drank, smoked, slept, and dug ditches with the U.S. Army, rode aboard a Navy aircraft carrier, and accompanied Marines on an island landing.

Pyle’s columns mentioned big battles, Allied victories, and even the occasional setback. But what endeared the native Hoosier to his readers — all 13 million of them — was his homespun way of chronicling the lives of everyday soldiers down to their hometowns. As he wrote in 1943, “I love the infantry because they are the underdogs. They are the mud-rain-frost-and-wind boys. They have no comforts, and they even learn to live without the necessities. And in the end, they are the guys that wars can’t be won without.”

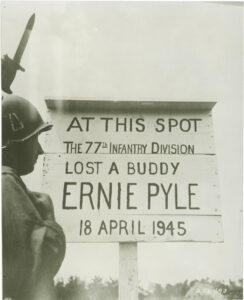

World War II ended on Sept. 2, 1945, but Ernie Pyle didn’t get to write about it. While riding in a jeep on the Japanese island of Ie Shima, he came under fire from an enemy sniper and was shot to death on April 18, 1945 — just six days after the passing of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and 80 years ago this month.

Memorial tributes were issued from all corners of the nation, starting from the top. Newly sworn-in President Harry S Truman said, “No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told.” Other dignitaries joined the chorus, including Generals Omar Bradley and Dwight D. Eisenhower, who would succeed Truman as president, and widowed First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

American newspapers gave Pyle a hero’s farewell with expansive front-page coverage and stirring editorials. The Tampa Times hailed him as the “chief spokesman for the fighting GIs” and asserted that “he will rest well — in a glory that will not be forgotten for decades.”

A dwindling collective memory

Eight decades later, however, it’s not so much a question of how many Americans remember Ernie Pyle’s glory, but rather, how many knew about it in the first place. “If you have no memories of World War II, you may not recognize the Pyle name,” wrote a New York Times reporter in 2011, two years after the State of Indiana closed Ernie Pyle’s birthplace. The rationale for withdrawing state funding was that the home — now owned and operated by the nonprofit Friends of Ernie Pyle — had drawn only 1,000 to 1,500 visitors annually.

But the reporter’s point is well taken, for the same reason that life insurance companies keep actuarial tables. Of the 16.4 million U.S. veterans of World War II, fewer than 1 percent (about 66,000) were alive in 2024, with a median age of about 98 years old, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. As the National WWII Museum website reminds us: “Every day, memories of World War II … disappear.”

That is unless they’re shared with subsequent generations. Author David Chrisinger did his part with his 2023 book, “The Soldier’s Truth: The Story of Ernie Pyle and World War II,” in which he retraced Pyle’s steps through the old battlefields where the Hoosier war correspondent once plied his craft.

But as Chrisinger sheepishly admitted, he didn’t recognize Ernie Pyle’s name the first time he heard it from a tour guide on Okinawa, where he was researching a story about his grandfather’s military service. Worse yet, he mistakenly associated Pyle with a very different kind of military operation. “Is this the guy that they based Gomer Pyle upon?” asked Chrisinger, recalling the cheerful bumpkin played by Jim Nabors in the popular 1960s sitcom “Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.” and “The Andy Griffith Show.” Dumbfounded, the tour guide said, “If you want to understand what your grandfather went through, you’ve got to read Ernie Pyle.”

Then again, it’s a safe bet that many of those reading this story would also have drawn a blank if asked to identify Ernie Pyle. Yet the war correspondent was so famous in the 1940s that anyone asking, “Who’s Ernie Pyle?” would have sounded as clueless as a current Hoosier asking, “Who’s Dave Letterman?”

At the pinnacle of his success, his syndicated column appeared in 400 daily and 300 weekly newspapers and was often the best-read item in the paper. The power of his popularity was evident in the dizzying array of career highlights that Pyle experienced in 1944, including a Pulitzer Prize for “distinguished war correspondence”; the publication of “Brave Men” — the third of his four books featuring some of his best wartime columns; making the cover of TIME magazine, which also wrote a profile about him; and the selection of Burgess Meredith, then an Army captain on active duty, to play him in a Hollywood film, “The Story of G.I. Joe.” Meredith’s physical attributes helped him secure the part — the slightly built journalist, who was in his 40s during World War II, stood only 5-foot-8 and weighed 115 pounds.

Pyle was so well known that he even appeared in a 1944 magazine advertisement for Chesterfield cigarettes above the caption: “On every front I’ve covered … with our boys and our allies, Chesterfield is always a favorite.”

It was all heady stuff for the former farm boy whose yen to see the world resembled that of George Bailey, the Jimmy Stewart character in “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

“But Ernie was George Bailey who got out,” said Ray Boomhower, senior editor of Indiana Historical Society Press. That hadn’t surprised Pyle’s family. “He always said the world was too big for him to be doing confining work here on the farm,” his father told TIME magazine. Even so, Pyle spent nearly all of his first 23 years on Hoosier soil.

Satisfying his wanderlust

Ernest Taylor Pyle — the only child of tenant farmers William C. and Martha Taylor Pyle — was born in 1900 on an 80-acre grain farm southwest of Dana in rural Vermillion County, not far from the Illinois state line. The family moved to a white farmhouse when he was 18 months old, and Ernest, as his relatives called him, resided there until his 1918 graduation from tiny Helt Township High School. In an era before the yellow school bus, Pyle often rode his favorite mare, Cricket, to the school building 3 miles south.

After high school, he enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve Force. But World War I ended before he could complete his training, so he enrolled at Indiana University in 1919.

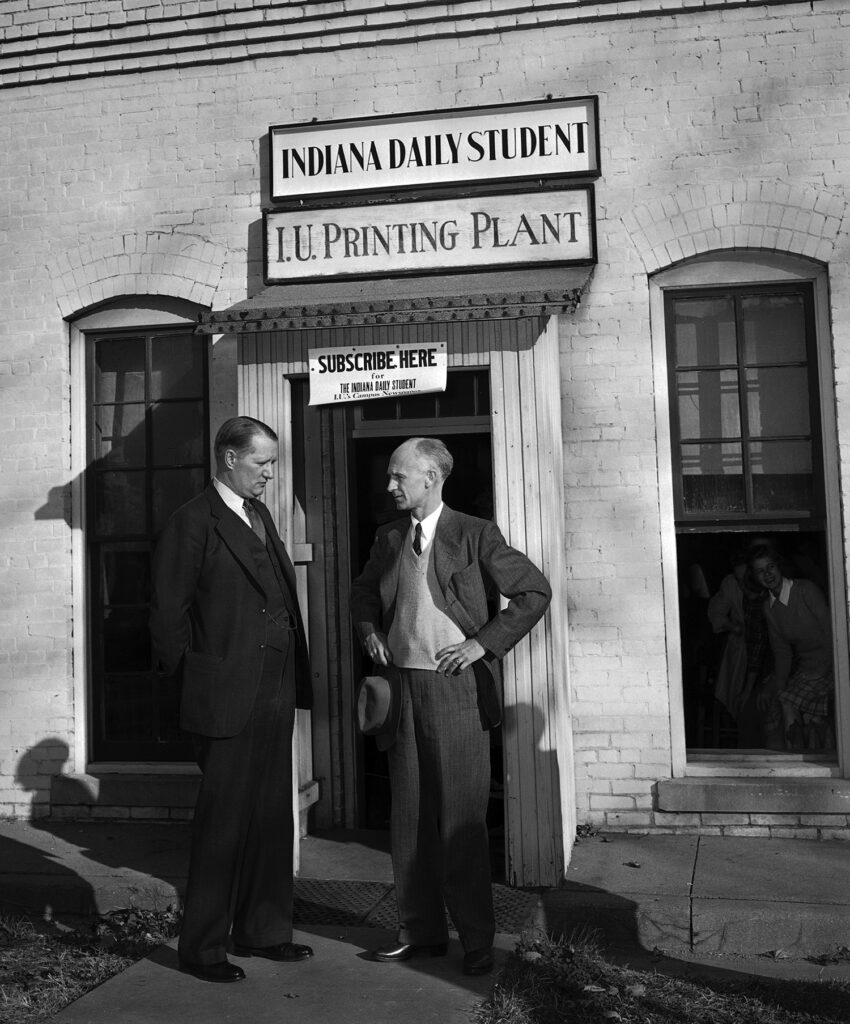

Pyle didn’t major in journalism. He couldn’t — IU didn’t offer a journalism degree until 1932. He majored in economics and started signing up for journalism classes as a sophomore. Pyle later said, “I took journalism at Indiana University because it was a cinch course and offered an escape from a farm life and farm animals.” Yet he would serve as editor-in-chief of the IU student newspaper, join the journalism fraternity — Sigma Delta Chi, and become a $25-a-week reporter for the La Porte Daily Herald — leaving IU in early 1923 with just one semester to go.

Four months later, the young reporter was on the move again, this time to the Washington Daily News in the nation’s capital. In 1925, he married Geraldine Elizabeth “Jerry” Siebolds, whom he’d met at a Halloween party, and the following year, the restless Pyle quit his job, bought a new Model-T Ford roadster, took his new bride on a tour around the country, and as he recalled, “wound up six weeks later in New York, broke. Had to sell the new Ford for $150 to get money for the next meal.” After brief stints with two New York City newspapers, he made a momentous decision to rejoin the Daily News

in 1927.

His interest in the burgeoning field of aviation prompted him to launch the first-ever daily column devoted to the subject, which wound up in syndication with Pyle as aviation editor for the entire Scripps-Howard newspaper chain. Flying more than 100,000 miles, he tackled topics ranging from airmail pilots to whether passenger flights would ever be profitable and gained no less a fan than Amelia Earhart — who once remarked, “Not to know Ernie Pyle is to admit that you yourself are unknown in aviation.”

A promotion to managing editor in 1932 marked the end of the column, but after three years of office work, Pyle contracted influenza and found his way back to column writing. During a recuperative leave of absence, he hit the road with Jerry and returned to write 11 stories about his experiences. An editor sensed “a sort of Mark Twain quality,” and Pyle soon traded his desk job for a gig that catered to his wanderlust. “I am a roving reporter,” he once explained. “Go where I please, write what I please, and keep no office hours.”

His syndicated column ran six days a week under several titles, including “Roving Reporter,” “Hoosier Vagabond,” and “Vagabond from Indiana,” and frequently mentioned wife Jerry — variously identified as “the Girl Who Rides With Me,” “That Girl Who Travels With Me,” or simply “That Girl.”

They spent five years on the road, crisscrossing the country 35 times in an era before interstates, roadside McDonald’s, and other amenities that modern-day travelers take for granted. “This was Depression-era America,” Chrisinger said. “He was driving on dirt roads most of the time.”

For Americans struggling to put food on the table, Pyle provided a daily escape with reports from

such far-flung localities as Alaska, Hawaii, South America, and the Panama Canal.

Readers appreciated his folksy writing style, his attention to unsung people and places, and his self-effacing persona — a “prose Charlie Chaplin,” as TIME magazine put it.

Reports from the front lines

But the onset of World War II took Pyle to more distant destinations with life-and-death dramas. Yearning to write more consequential columns, he journeyed to England in 1940 to cover the Battle of Britain. He vividly described a German bombing that left “London stabbed with great fires, shaken by explosions, its dark regions along the Thames sparkling with the pinpoints of white-hot bombs.”

When American forces entered the war in 1941, Pyle went with them. He toted a manual typewriter and submitted several stories at a time by military mail or by having them read over a shortwave radio. His Hoosier roots inspired occasional analogies, as when he compared a group of tanks preparing for battle to “the cars lined up at Indianapolis just before the race starts” and likened Okinawa to “Indiana in late summer when things have started to turn dry and brown, except that the fields were much smaller.” But his most memorable columns detailed the plight and sacrifice of the average GI.

In Pyle’s most acclaimed effort, “The Death of Captain Waskow,” he painted a haunting picture of soldiers mourning the loss of a beloved young officer who perished in Italy: “He reached down and took the dead hand, and he sat there for a full five minutes, holding the dead hand in his own and looking intently into the dead face, and he never uttered a sound all the time he sat there. And finally he put the hand down, and then reached up and gently straightened the points of the captain’s shirt collar, and then he sort of rearranged the tattered edges of his uniform around the wound. And then he got up and walked away down the road in the moonlight, all alone.”

A lasting legacy

In 2011, the National Society of Newspaper Columnists voted “Captain Waskow” the top American column in history. If nothing else, the honor attested to the staying power of Ernie Pyle in the 21st century, at least among fellow journalists.

Whether that applies to the public at large on the 80th anniversary of his passing is less certain. It wasn’t always so — Pyle’s death in 1945 prompted an outpouring of buildings, roads, schools, and even military equipment named in his honor, including a troopship and a B-29 Superfortress.

Nowadays, Pyle lends his name to streets in Galax, Virginia; Fort Meade, Maryland; and Fort Riley, Kansas, along with a middle school and a public library in Albuquerque that occupies the only house Pyle and his wife ever owned. Two elementary schools in California and one in Indianapolis bear his name, but two others in Indiana have closed since 2010 — the first in Gary and the second, ironically, in Vermillion County, where he was born and raised.

Fortunately, Vermillion County still boasts Pyle’s birthplace and museum in Dana. It’s planning an adjoining Ernie Pyle and Veterans Memorial Park — not to be confused with Ernie Pyle Rest Park, which just happens to be located near a stretch of U.S. 36 known as the Ernie Pyle Memorial Highway. Pyle’s name also adorns a travel plaza on the Indiana Toll Road and an island in Cagles Mill Lake. Even Captain Waskow has a high school named after him in Texas, a testament to Pyle’s influence.

Perhaps it falls to current residents of Pyle’s home state to serve as keepers of the flame. In addition to his birthplace in Dana, the Indiana State Museum periodically displays some Pyle possessions, including one of his typewriters.

And nowhere is his legacy stronger than at Indiana University, home of Ernie Pyle Hall, the former journalism school building, and a Pyle statue outside Franklin Hall, where tomorrow’s reporters — some known as Ernie Pyle Scholars — hone their talents at the Media School. Students can also take an Ernie Pyle class that travels to Europe on spring break to follow his path. “If you ever go to IU [for journalism],” said Boomhower, “it’s hard not to be influenced by Ernie Pyle.”

True Ernie Pyle fans can collect a 16-cent Ernie Pyle stamp issued in 1971 and an Ernie Pyle G.I. Joe, complete with a typewriter, created for Hasbro’s D-Day Collection in 2001. And the 1945 Ernie Pyle movie, “The Story of G.I. Joe,” can still be seen occasionally on cable movie channels — and free anytime on YouTube. Pyle, an advisor on the film, never lived to see it, nor did the movie include his death.

Ernie Pyle will also be remembered this month in a place far from Indiana. The American Legion post in Okinawa has held a memorial ceremony in his honor each year since 1952. Though Pyle is buried in Hawaii, participants gather at the Ernie Pyle Monument on the island of Iejima, its current name.

The Tampa Times predicted in 1945 that Pyle’s glory would not be forgotten for decades. Although Ernie Pyle deserves greater historical prominence, it’s heartening to know that he won’t be forgotten in this decade. Author Chrisinger discovered as much in 2019 when his online New York Times story about Pyle received more than a million views by the second day.

Apparently, the legacy of the farm boy from Dana still resonates. A 2020 documentary by WTIU, “Ernie Pyle: Life in the Trenches,” summed it up: “From an accomplished Indiana University alumnus to a celebrated national newspaper columnist to the world’s most widely read war correspondent, Ernie Pyle was truly America’s storyteller.”

Editor’s note: Want to read some of Ernie Pyle’s work? Check out his most famous and most widely-reprinted column, “The Death of Captain Waskow” here. Source: Indiana University

You can also visit erniepyle.iu.edu to read more of his wartime columns and see a photo gallery of Pyle throughout the years.