By Richard G. Biever

Pioneering aviator Amelia Earhart is remembered most for how her life ended. Her tragic disappearance over the Pacific while trying to girdle the globe in 1937 remains a mystery that still evokes a sense of wistful sadness and loss.

But her most endearing legacy, especially at Purdue University where she was a visiting faculty member, will be the boundless spirit in how she lived.

Earhart was a barrier-breaking pilot and an early advocate for women’s rights. She remains an inspiration, not just to women, but to all who passionately pursue their dreams.

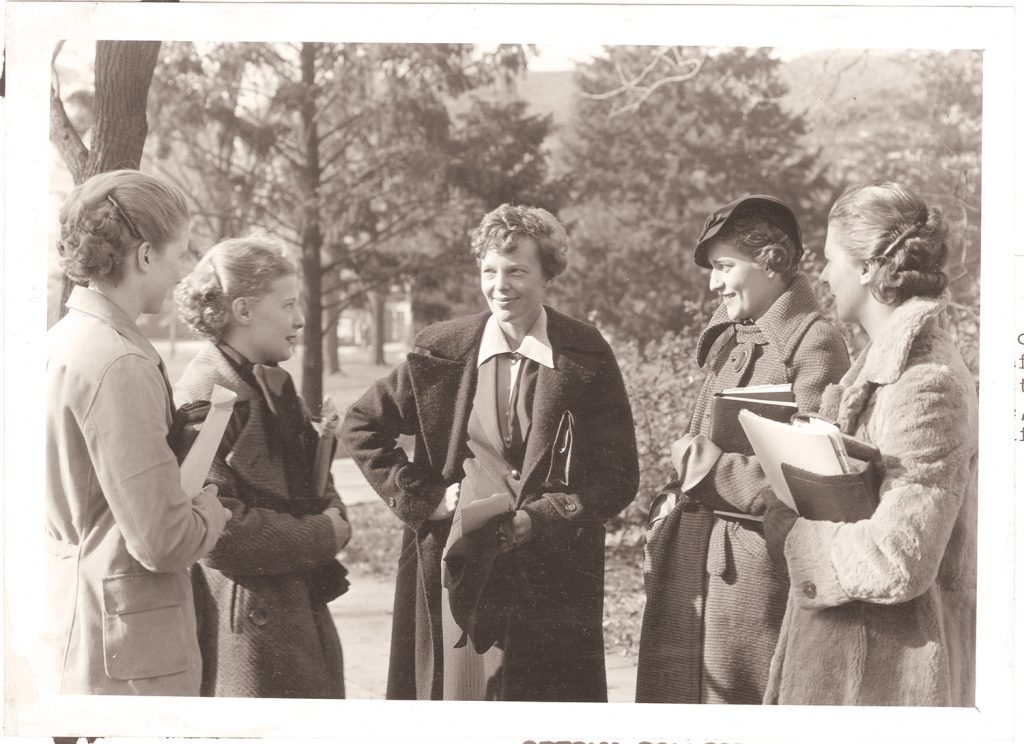

“She is most known for the disappearance,” said Tracy Grimm, archivist for flight and space exploration at Purdue University’s archives and special collections. “But if people really get interested, they will be pleasantly surprised when they learn how deeply she was committed to women’s issues. She really took time with young women, with students here on campus. She didn’t have to come here and be a counselor for women. But she did. And it seems it was important to her.”

At Purdue, she was both a career counselor for women and an advisor in the aeronautical engineering department from 1935 through her final flight. The plane she was piloting when she disappeared, nicknamed the “Flying Laboratory,” was funded by Purdue’s foundation and its supporters.

This July marks the 125th anniversary of Earhart’s birth, and the 85th commemoration of her disappearance. In pursuing her interests outside the realm of her contemporaries, Earhart pushed the boundaries. She gave women 15,000-foot views of all that was beyond traditional “women’s roles.”

“We have lots of students who come to Purdue because they know Amelia was associated with aeronautical engineering,” Grimm said. “Amelia existed in that time when women were right on the cusp of gaining more rights and being seen as human beings who could do anything a man could do.”

Grimm noted Earhart was not without detractors. “Amelia did face criticism. She faced people who maligned her in the press and said she couldn’t do things, or shouldn’t be doing things,” she said. “She represents courage in not taking ’no’ for an answer, pushing boundaries, and being herself, being true to her interests. That resonates with young women today, too.”

Eyes on the skies

Purdue University Airport was the first university-owned airport in the United States and the site of the country’s first college-credit flight training courses. In 1930, inventor-industrialist David Ross donated a tract of land to be used as an aeronautical education and research facility at Purdue University. Into this academic atmosphere, Earhart was eagerly welcomed by Purdue’s president, Edward Elliott, in November 1935.

In the fall of 1934, Earhart and Elliott were both invited by The New York Herald Tribune to speak at a women’s conference. After giving his speech, Elliott stayed to hear Earhart, who was already world famous for her flying exploits. She spoke about the future of aviation and women’s roles in the industry. As she spoke, Elliott realized she was the perfect role model for the female students enrolled at Purdue.

Elliott’s views on women were radical for the time. He was dedicated to preparing his female students for careers outside the home.

The Herald Tribune arranged a dinner meeting with Elliott and Earhart and her husband, George Putnam. After dinner, Elliott asked Earhart to join his staff at Purdue as a visiting faculty member.

Elliott later presented Earhart with a list of the six conditions of Earhart’s proposed position at Purdue, most of which concerned her duties as counselor in Careers for Women. Toward the end of that list, he casually mentioned that she would also serve as chief consultant for work in aeronautical engineering.

The document made it clear that Purdue recruited Earhart mostly as a mentor and role model for women, not for her knowledge of aviation. She did not see this as an insult, but rather a challenge. According to Putnam, when Elliott spoke to Earhart of his concern that Purdue’s female students weren’t keeping abreast of the “inspirational opportunities of the day nearly as well as they might be,” Earhart’s “eyes shone at the suggestion of a challenge.” And, according to her husband, Earhart regarded her short time at Purdue University as “one of the most satisfying adventures of her life.”

Earhart took her new role to help woman prepare for careers seriously. She handed out a survey and found 92% of the women on campus wanted a career. Her job, as she saw it, was to help their dreams take flight.

She loved the campus atmosphere. During her weeklong visits to West Lafayette each semester, Earhart stayed in a dorm room at Duhme Residence Hall, living and having dinner alongside the female students. Today, just down First Street from Duhme Hall is a larger-than-life bronze sculpture of Earhart holding a propeller. It was erected in 2009 outside a dining hall that also bears her name.

Whether she expressly meant to, Earhart served as a role model for many young women, not just aspiring aviators. From Earhart’s short, wind-blown hair to her wardrobe, the young women on campus wanted to emulate her. One story told is that when a group went to the dean of women to ask if they could wear slacks, as Earhart usually did, their request was met with the tactfully mild reproach and promise: “When you fly an airplane solo across the Atlantic, you may wear slacks on the Purdue University campus.”

Earhart viewed her accomplishments not only as personal achievements, but as feats for women everywhere. “Someday,” Earhart said, “people will be judged by their individual aptitude to do a thing and (society) will stop blocking off certain things as suitable to men and suitable to women.”

It’s been said that Earhart had a knack for navigating the world within societal limitations of the time while simultaneously defying them. She figured out how to present herself as a barrier breaker without being abrasive. For that, she was admired by men and women alike.

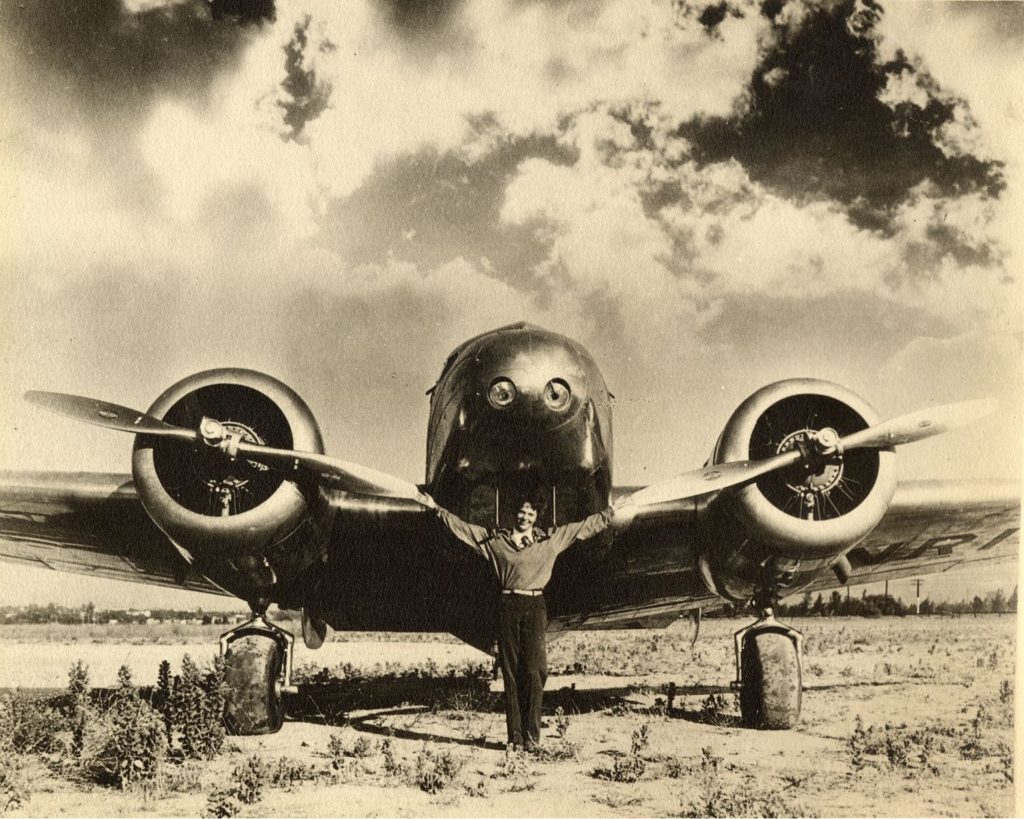

Though Earhart focused her time at Purdue primarily on counseling, Purdue’s Research Foundation funded her “Flying Laboratory,” an aircraft for her flight around the world planned for 1937. The Foundation contributed $80,000 from illustrious Purdue alumni and corporations with the defined objectives of collecting scientific and engineering data during the flight itself as well as during its preparation. Part of the goal was also to better understand the rigors long-range flight put on a body. Purdue stood to gain from the wide public attention as it sought to enhance its expertise and reputation as an aeronautical proving ground.

The plane, a Lockheed Model 10 Electra, was prepared for her around-the-world flight attempt in Hangar 1 at Purdue and in California. Earhart performed many of the tasks herself. For the flight, the plane had to be modified to add fuel capacity and lightened.

Originally, the global flight was to start and end at West Lafayette in the spring of 1937, according to a map published in The New York Herald Tribune. Flying west, the trip was aborted after reaching Hawaii. On March 21, on takeoff to the tiny central Pacific atoll known as Howland Island, a tire blew before the Electra left the ground. The plane “ground looped,” damaging the propellers, and had to be shipped to California for repairs.

With the delay, Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, changed plans. Once the plane was repaired, they flew to Miami and began their second attempt from there on June 1, flying first to South America, then east across the Atlantic to Africa, India and Australia.

After stopping in New Guinea, they began the longest and most perilous leg of the 29,000-mile journey on July 2, 1937. It was to be a 19-hour flight of 2,600 miles over the open Pacific. Their target was Howland Island, the same tiny uninhabited coral rock to where she was taxiing for takeoff when her plane was damaged in Hawaii. The cucumber-shaped island was barely more than a half-square mile, just big enough for the landing strip that had been prepared for her. The U.S. Coast Guard cutter Itasca waited near the island to assist. But the flight never arrived at Howland.

That morning, the ship received strong radio signals from Earhart which indicated the Electra was in the vicinity. But Earhart radioed that they were unable to hear any two-way communication. She said they were unable to locate the island or the ship, and they were running low on fuel. That was the last message the Itasca received.

Legacy

Earhart loved writing poetry. But the only poem of hers published while she was living was aptly called “Courage” (please see below). The 1928 poem summarized her view about life: That it’s better lived with the courage to push oneself, to break beyond “gray ugliness,” to “dare the soul’s dominion.”

Earhart lived her life with boundless courage, charting new courses for herself and all women. Seemingly the only barriers she couldn’t overcome were the mechanical limitations of her plane and a faulty two-way radio receiver.

Her writings and so much more can be found in the world’s largest collection of Earhart-related items at Purdue University’s Archives. The collection of some 3,500 papers, memorabilia, scrapbooks, photos and artifacts was donated to Purdue by her husband in 1941.

In the collection is a telegrammed press release from the New York Herald Tribune Syndicate dated July 3, 1937, the day after she disappeared. It had the exclusive details of her decision to discontinue flying upon completion of her world flight. “I have a feeling that there is just about one more good flight left in my system,” she told the reporter before departing on the trip. “I hope this trip around the world is it. Anyway, when I have finished this job, I mean to give up long distance stunt flying.”

The story also indicated her next plans were to carry out an intensive flight research program at Purdue.

Grimm notes Earhart’s love of Purdue was evident, too, by her husband’s gift. “He said she would have wanted her papers to be at Purdue University.”

Though Earhart’s earthly remains have never been found, her body of work and her spirit still reside — and still inspire — at Purdue. And all of Indiana is richer for the connection.

RICHARD G. BIEVER is senior editor of Indiana Connection

Courage

Courage is the price that Life exacts

for granting peace.

The soul that knows it not,

knows no release

from the little things:

Knows not the livid loneliness of fear,

Nor mountain heights where bitter joy

can hear

The sound of wings.

How can life grant us boon of living,

compensate

For gray dull ugliness and pregnant hate

Unless we dare

The soul’s dominion? Each time we

make a choice, we pay

With courage to behold resistless day,

And count it fair.

AMELIA EARHART, June 1928

The poem and historical Amelia Earhart photos are used with permission courtesy of Purdue University Libraries, Karnes Archives and Special Collections.

Amelia Earhart Timeline

July 24, 1897

Amelia Earhart is born to affluent parents in Atchison, Kansas. Her father is a lawyer for the railroads.

Jan. 3, 1921

Begins flying lessons.

July 1921

Purchases her first plane.

June 17-18, 1928

Becomes first woman to fly across the Atlantic.

Feb. 7, 1931

Marries George Putnam, who becomes her manager.

May 20-21, 1932

Becomes first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic.

November 1935

Accepts invitation to become a visiting faculty member at Purdue University as a career counselor and aviation advisor.

March 17, 1937

Begins her first attempt to fly around the world, going west to east, but damages her plane on takeoff in Hawaii.

June 1, 1937

Leaves Miami on a second attempt, this time heading south and east, to South America, Africa, India, and New Guinea.

July 2, 1937

Departs for Howland Island in the central Pacific. At sunrise, she and navigator Fred Noonan radio they cannot find the island and cannot hear radio transmissions.

July 19, 1937

Official search efforts for her and Noonan end.

Jan. 5, 1939

Is officially declared dead.