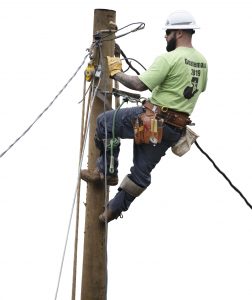

PHOTOS AND STORY BY RICHARD G. BIEVER

The last morning 14 Indiana electric cooperative linemen would spend at their worksite in rural Guatemala, Clay Smith was handed a guitar at the hotel that had been their home for two weeks. The 33-year-old line foreman at Whitewater Valley REMC sat down in one of the worn armchairs in the entryway and started squeezing a few notes from the instrument’s dull nylon strings.

Then, he started into the Top 40 hit from 1971 — “I’d Love to Change the World.”

“If I’m sitting around a campfire, that’s always my ‘go to’ song,” Clay said later. “It was the very first song my stepdad ever taught me how to play. It’s the one I took the time to learn from beginning to end.”

Marshall County REMC lineman Doug MacLain recognized the tune, looked up the lyrics on his cell phone, and both he and Clay started singing. “We were just in the moment, not even paying attention to what the song actually was saying,” Clay recalled. “Then one of the guys said ‘are you listening to the words?’”

That’s when the lyrics connected with the crew’s accomplishments in Guatemala.

“I’d love to change the world …”

Two days earlier: The crew turned the power on in the tiny village of San Jacinto, a dusty half-hour’s ride north on bumpy gravel roads from their hotel. Two weeks earlier: San Jacinto’s electric system was just 50 bare poles. They had been set but were awaiting the wires, transformers and hardware, and the arrival of the Hoosiers. In the two weeks, Indiana linemen built 4.3 miles of power lines and wired almost 90 homes, two churches and a school.

“… But I don’t know what to do…”

A day earlier: The crew turned the water back on at San Jacinto’s neglected pumping station. Months earlier: The 2-year-old diesel generator and electric pump stopped working. A question arose over who was responsible for repairs: the village or the municipality of Chahal, so nothing was done. Villagers resorted to making the long slog with containers to the stream that flows past the village to collect water, wash clothes and bathe. The Indiana crew took it upon themselves to fix it, and did.

“… So I’ll leave it up to you …”

The Indiana line crews had already changed the world in San Jacinto. And they shared what they knew with thankful villagers eager to continue what the Hoosiers started.

A better tomorrow

The 14 lineworkers, along with four project managers and support staff, traveled to Guatemala March 24 as part of the continuing initiative — “Project Indiana: Empowering Global Communities for a Better Tomorrow.” In cooperation with NRECA International, Project Indiana’s mission is to bring electricity to developing rural areas of Guatemala, and provide the necessary knowhow the nascent utilities need to sustain themselves and grow. The group returned to Indianapolis April 9.

San Jacinto is a village of about 150 families tucked amid rolling hollows and perched along steep hillsides of knobby karst landscape in eastern Guatemala. The villagers there live mostly through subsistence agriculture. They grow corn in small fields and in any patch of soil between craggy outcrops of rocks up the steep hillsides where it’s planted by hand. They produce beans, cardamom, chili, cacao (from where cocoa comes), bananas and other fruits, and raise chickens, pigs, and cattle.

This was the fourth excursion Indiana co-ops made to Guatemala since August 2012. Since Project Indiana began putting boots on the ground and up the poles and into the clouds, 70 Indiana lineworkers have now brought power to over 500 rural homes, four schools, and five churches.

“Words and pictures don’t do it justice,” said Jamie Bell of the harsh life the crews find in Guatemala’s countryside. “You see how hard they work for the little they have.”

This was the second Project Indiana trip for Jamie, a lineman from NineStar Connect, who served as a coordinator on this trip. “Electricity,” he added, “gives them a powerful tool to better themselves — to make them want to stay there. With it, they’ll have better health, better schools, just an all-around better way of life.”

Long time coming

Electricity came to the Las Conchas area near San Jacinto in 2009. That’s when the Guatemalan government worked with Japan to build three small hydroelectric generating stations along with distribution systems in three different areas. Service was built to 12 small communities in the area, but the power line stopped just short of San Jacinto.

Enrique Rax Yat, 45, a community leader in San Jacinto, began asking the electric utility to extend service six years ago. When Indiana turned the lights on April 2, he and his wife were home. “It was beautiful,” he said. “I prayed, ‘Thank you, God, for this achievement.’”

Through an interpreter, Enrique said he hopes electricity will encourage more younger folk, including his own four children, to stay there. “Maybe people will not need to leave,” he said. “They will be looking for better opportunities here.”

“Some people will go to different states here in Guatemala,” said Erick Berganza, the Guatemalan engineer with NRECA International who designed the electric system for San Jacinto. Erick also worked alongside the Indiana crew for the two weeks. “But a lot will go to the United States. They know that if they go to work hard in the U.S., they will make a lot more money than they will here.

“We’re trying to help these people have better opportunities,” Erick added. “Electricity is an opportunity to have a better life here.”

A model community

Unlike previous project trips, Project Indiana included an agreement that every home that it wired in San Jacinto was to have a cooking stove installed. While the simple stoves will burn the area’s abundant wood, they will have stove pipes to ventilate the kitchen and living quarters.

“We’re excited to help you bring electricity to your homes,” Project Indiana’s board president Ron Holcomb told San Jacinto’s residents at a town meeting the day the crew arrived, “and we’re also very excited that you are going to have stoves in your homes.”

Ron, Jamie, and Hugo Arriaza, a Project Indiana contractor from Guatemala, attended a Chahal municipality council meeting the evening after the lights were turned on. They were invited to discuss how Project Indiana, the local government, and the electric utility could cooperate on providing the stoves and other improvements to the village, such as converting the diesel generator-powered water pumping station to total electric.

“San Jacinto will be a model community for others,” said Hugo.

One Saturday morning during the project, Ron and Hugo held an informal seminar at a nearby school on sustainable electric utility management. Community representatives that make up the electric utility — Farmer’s Development Association Las Conchas — attended along with interested consumers and past representatives.

In the course of the three-hour class, slowed by the translation from English into Spanish and the Mayan dialect called q’eqchí, which is the main language spoken in the area, Ron discussed how electric cooperatives work in the U.S. He noted running a utility is a capital-intensive job that requires securing financing, growing the number of consumers, and setting rates appropriate to maintain the assets and infrastructure.

“Someday, we want to come to Guatemala to drink cervezas with you. We don’t want to keep coming to build power lines,” he quipped.

“Building poles and wire is just the beginning. They have to run a sustainable utility,” Ron said later.

While in Guatemala, Ron and Hugo also met with utility leaders from the three other utilities with which Project Indiana has worked to begin planning a multi-day conference to delve deeper into sustainable management practices for the directors and officials.

Part of a family

The final day in San Jacinto, the Project Indiana crew was celebrated like the heroes they were — surrounded by hundreds of folks, young and old, who gathered and watched from the sparse midday shade along the walls of the Catholic church and other buildings. Incense and Mayan dancing preceded the procession of the crew to a makeshift stage in front of the building that served as the utility warehouse. The Guatemalan and U.S. national anthems were played and a prayer was said. Local officials praised and thanked them.

“San Jacinto, you are now part of the Project Indiana family,” Ron told the gathering when invited up for some comments. “And now, we are also part of your family.”

On the eight-hour drive back to Guatemala City for the flight home, Travis Goffinet, a lineman with Southern Indiana Power on his second trip, reflected: “The hardest thing about the project is you don’t get to see the fruit of your labor. We built the power line, which was the goal, but it wasn’t the main goal. The main goal is to try to change their lives, and you don’t get to see that.”

“I would be interested to see what that place does in the next 10-15 years,” added Clay, “to see how they move forward.”

In other words, Clay and his co-op cohorts want to see just how they changed the world — or at least changed San Jacinto.

RICHARD G. BIEVER is senior editor of Indiana Connection

About Guatemala

The Republic of Guatemala is located south and east of Mexico’s southern border and is the largest of the seven Central American countries.

Size: Guatemala encompasses about 42,043 square miles, a bit bigger than the state of Ohio.

Population: 16,581,273 (2018 est.) More than half of its population lives below the poverty line.

Capital:Guatemala City

Government divisions:Guatemala is divided into 22 departments (akin to states in the U.S.) which are sub-divided into about 335 municipalities (akin to U.S. counties).

Besides Guatemala itself, the Guatemalan national anthem includes the name of only one other political state … Indiana!

The eighth and final stanza of the anthem, written in Spanish and adopted in 1896, begins with “Ave Indiana,” which is translated to “Native Bird.” The line continues with “that lives in your seal, the protector of your soil…”

The “native bird” to which the stanza refers is the resplendent quetzal, a colorful Central American rainforest bird that has a long tail. As the anthem says, the bird figures prominently in Guatemala’s national seal, on its flag, and on its currency as a symbol of liberty. In Mayan culture, the quetzal’s tail feathers were traded as currency, and Guatemala’s currency today is the quetzal, named after the bird.

Sources: Indiana Connection, Wikipedia and other various internet sites

2019 Project Indiana crew

Making the trip to Guatemala were:

Matt Bassett, Carroll White REMC

Kevin Bay, Johnson County REMC

Michael Bowman, Boone REMC

Brent Buckles, Northeastern REMC

Ethan DeWitt, Northeastern REMC

Jason Gates, Tipmont REMC

Travis Goffinet, Southern Indiana Power

Chad Griffin, South Central Indiana REMC

Matt Huck, NineStar Connect

Doug MacLain, Marshall County REMC

Jason Morrison, Jackson County REMC

Tyler Powell, Henry County REMC

Josh Sawyers, South Central Indiana REMC

Clay Smith, Whitewater Valley REMC

The crew also included project coordinators and support staff:

Joe Banfield, Indiana Electric Cooperatives

Jamie Bell, NineStar Connect

Richard G. Biever, senior editor of Indiana Connection

Ron Holcomb, Project Indiana board president/president and CEO of Tipmont REMC

Support Project Indiana at projectindiana.org

Project Indiana is a 501c3 organization formed by Indiana’s electric cooperatives with the vision of helping developing global communities advance by adopting villages, bring them electric power and support them as they form electric cooperatives that enable them to enjoy a better way of life. Electrification projects are completed in partnership with NRECA International.

Visit ProjectIndiana.org to learn more and contribute.