Just a touch of tarnish may be creeping into his brass-plated crown. And the roundness of his waistline is a sure indication that he’s a child of the ’50s — now into his 50s. But the twinkle in his eye, the smile on his face, the ever-present wave will never age — nor will his dedicated service to rural electric cooperatives and their consumers.

Willie Wiredhand, the little guy with a light-socket head, push-button nose and an electrical plug for his bottom and legs, celebrated 50 years as co-op spokes-character and mascot in 2001. He’s still the friendly and inspirational golden boy who symbolizes dependable, local, consumer-owned electricity. He’s appeared in just about every type of cooperative publication and promotional item: signage, stationery, newsletters, annual reports and advertising, coffee mugs, watches, shirts, baseball jerseys, beach towels, night lights, bobbleheads and more.

He’s even been placed into Christmas ornament handcrafted by Electric Consumer readers for our annual ornament contest.

Though his presence on both the local and national stage has diminished in recent years in light of more advanced co-op marketing, Willie remains a viable and valuable conduit of information between many co-ops and their consumers.

“Willie is one of a long line of distinguished industrial spokes-characters that have been used to identify and personalize industrial products and services,” said Margaret F. Callcott, who has extensively researched and written about these gesturing little pluggers of the advertising world. “Many marketers of products and services would love to have a symbol as recognizable as Willie to distinguish them in the current marketplace. Those lucky enough to have these consumer icons at their disposal will do well to figure out how to leverage them in the new century.”

Of ‘loyal servants’ and gods

Willie’s actual birthdate is traced to Oct. 30, 1950. He was the creation of Andrew McLay, a free-lance artist for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association in Washington, D.C.

“We were toying with ideas for a rural electrification symbol,” recalled William S. Roberts in a tribute to McLay, who died of cancer at age 52 in 1974. Roberts was editor of Rural Electrification magazine, NRECA’s trade publication, in the 1950s. “I had tossed out the idea that the symbol ought somehow to portray rural electric service as the farmer’s hired hand, which in those days was almost the entire PR story we had to get across. Drew picked up both the idea and a sketch-pad one night at our home after a couple of beers.”

Sprawled out on Roberts’ living room floor, McLay gave birth to “Willie the Wired Hand.” NRECA’s membership selected Willie as their animated ambassador at their national meeting in February 1951. Willie’s name was soon shortened to “Willie Wiredhand.”

In the grand order of the spokes-character cosmos, Willie falls under the “product personification.” “These characters,” Callcott said, “were usually cast as ‘loyal servants’ of the consumer, deriving credibility from a message of dependability and devoted service.”

In the grand order of the spokes-character cosmos, Willie falls under the “product personification.” “These characters,” Callcott said, “were usually cast as ‘loyal servants’ of the consumer, deriving credibility from a message of dependability and devoted service.”

Willie came along in the heyday of animated advertising characters. Hundreds, promoting everything from bleaches to stomach antacids, were already in the marketplace. But Callcott tracked their rise to the late 1890s when a French tire company created a guy made of what looked to be stacked tires — the Michelin Man. And his tread hasn’t worn out yet. In fact, a live-action smiling Michelin Man is back in recent TV commercials driving in the rain and looking for his pet, a puppy with similar puffy rounded features, or lovingly inspecting each Michelin tire before it heads out the door.

“These characters exhibited personality … a friendly face and jolly demeanor with which consumers could develop a positive relationship,” Callcott wrote in her 217-page doctorate dissertation for the University of Texas at Austin in 1993. She explained that with the rise of mass production and mass transportation at the beginning of the 20th century, companies needed a way to distinguish their products and at the same time build trust among consumers. They filled both needs in the fabricated characters who spoke through the emerging mass media.

For whatever reason, people connected and responded to these characters. They touched on a human need to personify things. Today, Callcott, a research manager for Scripps Networks in Knoxville, noted, “By the time we reach adulthood, personification is ingrained in our psyche: we name our vehicles, our plants, our guns, and even our body parts, always seeking to relate to them on some human level, never quite believing that somehow they don’t have a soul of their own.”

The personification of animals and inanimate objects goes much deeper into human history, though. “This need to place ideas and objects on a human level dates back to ancient times, when gods were created to personify abstract concepts such as strength and love, as well as little understood natural forces like sunshine and thunder,” she said.

In modern times, personification allowed consumers to get to know new products and little understood services. Instead of the gods of war and harvest and love, into the modern pantheon came humanized symbols for snack foods, household cleansers, stomach antacids, canned vegetables and glue-all which people could know on a first name basis. Instead of Thor, Apollo, Demeter and Aphrodite came Mr. Peanut, Mr. Clean, Speedy Alka-Seltzer, the Jolly Green Giant and Elsie the Cow.

“Gas and electric companies in particular have had the challenge of personifying a very intangible product,” Callcott said. “Reddy Kilowatt, Willie Wiredhand, Katie Kord, Handy Heat and Miss Flame were among the many characters created to answer this challenge.”

Reddy vs. Willie

Electric cooperatives formed in the 1930s to bring electric power to the vast unserved areas of rural America. Though, most of rural America had power by 1949, many consumers were still in the dark when it came to understanding electricity and the ways it could improve the farm and the lives of farm families. To help get the message out, co-ops wanted a spokes-character, too, and turned to the leading industry spokesman, the fanciful Reddy Kilowatt.

Reddy had been around since 1926 and was used by 188 utilities in almost every state. He was depicted with a body, arms and legs of jagged red electrical bolts and had a round head with a light bulb for a nose and outlets for ears.

Reddy had been around since 1926 and was used by 188 utilities in almost every state. He was depicted with a body, arms and legs of jagged red electrical bolts and had a round head with a light bulb for a nose and outlets for ears.

The creator of Reddy, Ashton B. Collins, who licensed his character to private power companies, refused to let consumer-owned co-ops use the symbol. He cited power company propaganda that co-ops were “socialistic” because they relied on federal loans and didn’t want Reddy associated with them. Furthermore, Collins’ lawyers warned co-ops through a series of letters that any character co-ops created would infringe on Reddy’s exclusive patents and trademarks.

A year later, though, in 1950, NRECA pressed on believing its new creation — Willie — with his UL-like-approved body suggesting the practical application of electricity, was different enough from Reddy who represented the abstract idea of electrical energy. “Any similarity between trim, efficient Willie and the shocking figure of Reddy Kilowatt is purely coincidental,” one co-op official said.

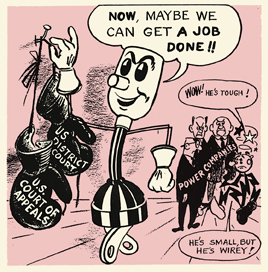

Willie’s creation and adoption by the electric cooperatives was a jolt to Reddy and the investor-owned utilities. After a couple of years of angry exchanges and increasing static between Reddy’s lawyers and Willie’s defenders, Collins and a coalition of 109 private power companies formed Reddy Kilowatt, Inc. Its first act was to file a lawsuit in South Carolina’s federal district court against young Willie on July 14, 1953. The suit charged co-ops of infringing on Reddy’s registered trademarks and practicing unfair competition in the electric utility industry. Reddy and company asked for an injunction to bar the use of Willie in co-op advertising and repayment of damages caused to Reddy’s owners.

In essence, Reddy and his legal henchmen were trying to pull the plug on Willie.

The gist of Reddy’s lawsuit was not in how Willie looked. Rather, Reddy’s lawyers argued that in marketing electricity, Willie’s poses so closely resembled Reddy’s that the public would be confused. Willie’s attorneys countered that long before Reddy, other animated characters had been in widespread use, even in the electrical industry, as trademarks and ad promotions.

From their beginning, co-ops had constantly fought skirmishes with private power companies attempting to thwart the success of non-profit utilities over territory and power supply. Appropriately, the battle between Willie and Reddy was symbolic of the David vs. Goliath struggle between co-ops and private power companies. “This is the most vicious thing that the rural electric systems have yet encountered,” quipped Clyde T. Ellis, NRECA general manager at the time. “We’re not fighting one or ten power companies this time. There are over a hundred of them suing us.”

In June 1956, a federal judge sided with Willie and the co-ops. Reddy appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals Fourth Circuit. A three-judge panel heard the case and, on Jan. 7, 1957, issued its unanimous decision reaffirming the lower court.

The court noted the similarities between their poses but added that Reddy has appeared in “thousands of poses doing almost everything humanly possible and in every conceivable activity.” The judges ruled, “The plaintiff has no right to appropriate as its exclusive property all the situations in which figures may be used to illustrate the manifold uses of electricity.”

Incidentally, the case also ended Reddy’s monopoly over other power companies. Testimony during the trials revealed that Reddy’s syndicate often acted like B-grade movie gangsters using threats of lawsuits and intimidation to keep other private power companies from creating their own spokes-characters. The Willing Watts from Arkansas Power & Light Co.; Eddie Edison by the Boston Edison Co.; Elec-Tric by Cincinnati Gas and Electric Co.; Mr. Watts-His-Name by Bradford Electric Co.; Mr. Watt-A-Worker, by New Orleans Public Service Inc., were just a few characters silenced by Reddy’s handlers.

Though Willie symbolized co-op friendliness, he also embodied co-op spunk, willing to stand up for what was right in the face of impossible odds. “He’s small, but he’s ‘wirey’” became part of Willie’s trademark which was granted by the U.S. Patent Office later in 1957. The registration allowed Willie to become the beloved character he remains today.

Baby boomer revival

By the 1970s, overall popularity waned in the use of spokes-characters. Most of the ones that remained were relegated to promoting sugary kid cereals and snack foods.

Reddy had a hard time adjusting to the energy crunches of the ’70s, as the demand for electricity began to exceed supply. Many power companies gave Reddy the pink slip, figuring the need for a strong marketing tool was no longer needed. Reddy was forced into semi-retirement.

Willie, on the other hand, donned a sweater and hopped on a bicycle in new ads to promote energy conservation. He was shown caulking and offering energy tips. But, before long, many co-ops viewed him, too, as outdated and placed him on a back shelf like an old appliance.

Then, around 1985, Callcott noted, there was a resurgence in spokes-character advertising. Charles Schulz’s Peanuts characters started successfully selling Metropolitan Life Insurance about the same time animation made a comeback with the hit movies, “The Little Mermaid” and “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?”.

Much of the rebirth was fueled by a sizable baby boomer market eager to recapture facets of its childhood, Callcott said.

She noted that in the trade publication Advertising Age, King Features Syndicate took out “work wanted” ads for old cartoon favorites Betty Boop, Popeye, Blondie and Family Circus, putting them up for hire with the nostalgia-oriented tagline, “Friends from childhood last forever.”

Hoping to capture the fancy of nostalgic baby boomers and position itself for what was expected to be the coming competition in the electric utility market, Northern States Power Co. brought Reddy Kilowatt out of retirement in 1998. The Minneapolis-based electricity provider, serving 1.4 million customers in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan and the Dakotas, bought the exclusive rights to Reddy from Ashton Collins Jr., son of Reddy’s creator, who was living in Albuquerque. Reddy, who was only being licensed to a handful of other companies at the time, still carried strong recognition as a dependable and trustworthy symbol of electric service, NSP reasoned.

Reddy was fitted with new sneakers and even given a sidekick, Reddy Flame, to promote NSP’s gas operations. The company also opened a Reddy Store, offering new and vintage collectibles and memorabilia with his image.

Reddy’s comeback as a full-fledged spokes-character, however, suffered a major black out shortly after his revival. Northern States Power merged in August 2000 with Denver-based New Century Energies under the name Xcel Energy, Inc. A spokesman said, “Reddy is in a bit of transition to his new employer, and right now his duties are mostly ceremonial (parades and safety demonstrations). We’re still working on how he will fit into the overall Xcel Energy strategy.”

‘A spokes-plug for all time’

Willie Wiredhand may not live on for millennia as the gods of mythology have. But, as this new millennium dawns, Willie’s place is secure in the hearts of many consumers.

“Although Willie and his many spokes-character friends may rise and fall in prominence over the years, I think we can be assured of their continued presence,” Callcott said.

“The landscape may change, but people do not lose their desire to feel a personal connection to products and services that permeate their lives. If anything, this need intensifies when distribution channels expand … as they did at the turn of the last century with mass production and mass transportation, and as they have at the turn of this century with the introduction of the Internet.

“Unlike human characters, such as Aunt Jemima and Betty Crocker, Willie does not require physical updating to maintain credibility,” Callcott continued. “As a plug, he still personifies electric power. As a spokes-character, he has come to represent a ‘brand’ of reliable electric power (consumer-owned vs. investor-owned).

“Willie,” she said, “is truly a spokes-plug for all time.”

Story by Richard G. Biever, senior editor of Electric Consumer. Willie Wiredhand is a registered trademark of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association and cannot be used without permission of NRECA.