By Emily Schilling

It was dark. The only light flickered through the globes of coal oil lamps. Food was prepared on wood stoves. Washing was done by hand and scrub board. And farm chores were tackled without the assistance of electrical equipment.

This was living in the country 85 years ago.

And living wasn’t easy for rural families. The conveniences of city life — the conveniences made possible by electricity — were not available to most country folks.

Power companies didn’t want to string their lines into less-populated rural areas. It would cost too much. Besides, they thought, farmers didn’t need electricity.

But the farmers knew differently. They knew how electricity could make them more productive. Farm wives, meanwhile, would no longer have to slave over a hot wood stove in the summer and press hand-laundered and line-dried clothes with a six-pound stove-heated “sad iron.”

Electricity could change things for them — change things for the better.

Roosevelt creates REA

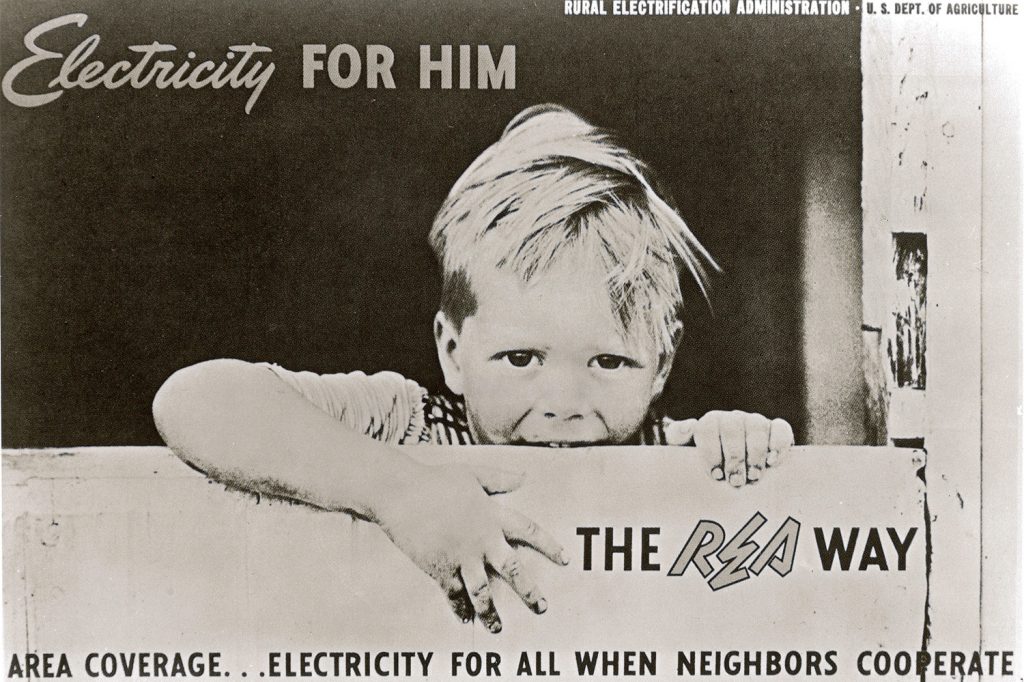

President Franklin Roosevelt knew about the hardships rural America faced. Only one famer in 10 had electricity. And Roosevelt vowed to do something about that. When he issued Executive Order 7037, which created the Rural Electrification Administration on May 11, 1935, the countryside finally had the promise for a better future.

The REA, Roosevelt explained, had a simple purpose: “to initiate, formulate, administer and supervise a program of approved projects with respect to the generation, transmission and distribution of electric energy to rural areas.”

It was the lifeblood for rural electric cooperatives which rural residents formed to bring power to the countryside. The order meant Congress could spend $1 million on rural electrification projects. It became the best investment the government ever made for rural America.

Though the REA was initially part of an unemployment relief plan, it became an independent lending agency with the passage of the Rural Electrification Act a year later. Roosevelt signed the act, authored by Sen. George Norris and Rep. Sam Rayburn, on May 20, 1936.

Rural electric cooperatives started in Indiana with the help of the Indiana Farm Bureau Cooperative and its general manager, I. Harvey Hull. Hull, who learned of the effectiveness of electric co-ops during a trip to the Scandinavian countries in 1934, spearheaded the effort to bring electricity to rural Indiana.

Hull helped author the Indiana REMC Act, which was passed by the Indiana General Assembly and signed into law by Gov. Paul V. McNutt two months before Roosevelt signed Executive Order 7037.

Members sign up

Co-op interest flourished in the state soon after the REMC Act was passed.

Men and women from throughout the state volunteered their time and powers of persuasion to sign their neighbors up for electricity. All it took was $5 to be a member of a rural electric cooperative.

Getting that $5 was not always easy though. After all, this was the height of the Great Depression and money was tight. Besides, many people were distrustful of this whole co-op idea. What if it failed?

Though it took some prodding and patience to get people signed up, with each new person, the building of lines moved closer to reality. Just as the farmers themselves did the signing up, so did they set — by hand — the poles that would carry the electric lines to rural Indiana. They volunteered long hours and sweat equity with the help of engineering crews sent out by Indiana Statewide REMC, a service organization set up by the Farm Bureau in 1935. (Indiana Statewide was reorganized as a service association for Indiana’s electric cooperatives in 1940. Today, the association is known as Indiana Electric Cooperatives.)

Through the 1930s and 1940s, lines were strung throughout rural Indiana and the nation. As homes were gradually energized and the countryside was aglow — not with the flicker from a coal oil lamp anymore but the constant light of a bare bulb — the power of the people, joining together for a cause, was lauded just as much as the power of electricity.

Life-changing experience

For those early electric cooperative members, the day their lights came on for the first time was an indelible life-changing experience. Clark and Lois Woody, whose rural Boone County farm was one of the first in the country to be electrified through REA-financed lines, received their electric meter on May 22, 1936.

“There were men everywhere — in all the rooms and closets, turning on all the lights and switches to make sure they worked; they weren’t sure it would work,” Lois Woody once said about her family’s first day in their newly electrified home.

Others remembered their awe when seeing a 25-watt bulb aglow for the first time, and their shock since the illumination unmasked dusty corners in homes once thought to be spotless.

After rural electrification, rural residents bought appliances they’d only dreamed about: refrigerators, toasters, radios and washing machines topped the list.

Still, most new electric consumers realized they were in the dark when it came to knowing anything about the new power. A common perception was that there was a limit as to how much electricity each consumer could use. Back in the 1980s, Edward Purtzer, former manager of Southern Indiana REC (now Southern Indiana Power) in Tell City, recalled, “We had a lady … that always used 35 kilowatts (a month). I learned she went up to 35, then turned everything off. She thought that was all she could use.”

Others would sometimes take their ironing to church since electrical use there was so low. And, they’d pull out their kerosene lamps whenever they thought they were using too much power.

A different kind of circus

But through a traveling appliance show called “The REA Circus” and electric cooperative annual meeting caravans, co-op members in rural electrification’s early days were invited to gather under the big top in a county fair atmosphere to learn about electric appliances, farm equipment and energy use. As many a 5,000 people a day would venture to the circus to marvel not at tigers and elephants, but newfangled electric timesavers.

For those in the country, throughout the country, finally getting electricity was a turning point toward a bright future. John Snyder, a rural electric pioneer from Henry County REMC, headquartered in New Castle, once said, “It was like a new world. Just like opening up a door into something you never expected to have.”

Eighty-five years later, we celebrate that new world and the pioneers who paved the way for the generations since.

EMILY SCHILLING is editor of Indiana Connection.