BY DIANE WILLIS

In the remote and rugged beauty of northeastern Guatemala, Hoosier lineworkers Brian AmRhein, from Decatur County REMC, on pole, and Doug MacLain, from Marshall County REMC, prepare to install the hardware on the pole to bring electricity to these village buildings.

Photo by Scott Sikora, Kankakee Valley REMC

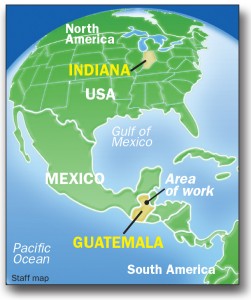

We take electricity for granted. We flip a switch, and there are lights. We push a button, and we connect with the world. This April, 14 Indiana linemen from 14 electric cooperatives — from Plymouth to Jasper, New Castle to Tell City — brought a village in Guatemala into the 21st century.

For two weeks, through a unique philanthropic initiative called Project Indiana, they faced a daunting task in extreme heat and brutal, mountainous jungles. But linemen, who have one of the world’s most dangerous jobs, are a unique breed. These men volunteered to go to one of the poorest, most remote parts of Central America, to do one thing: bring electricity to those who have never had it.

The 1,300 villagers of Sepamac in remote northeastern Guatemala live the simplest of lives. They endure extreme hardships. A whole family lives in a smoky, dark, one-room hut with packed dirt floors, light seeping in through bamboo or wooden slats — cooking and sleeping, living and eating all in one tiny space. They eke out a meager living, subsisting mainly on ground corn. Some grow cash crops of cardamom or pepper. They eat eggs or a little meat, once or maybe twice a week. They all lack protein — a basic need for their development.

It’s no wonder three-fourths of the children under the age of five in the village of Sepamac suffer from chronic malnutrition. Guatemala, in fact, has the fourth highest chronic child malnutrition rate in the world. Its poorest and most vulnerable people, like those in Sepamac, are indigenous natives who speak Q’eqchi’, a Mayan language.

It’s no wonder three-fourths of the children under the age of five in the village of Sepamac suffer from chronic malnutrition. Guatemala, in fact, has the fourth highest chronic child malnutrition rate in the world. Its poorest and most vulnerable people, like those in Sepamac, are indigenous natives who speak Q’eqchi’, a Mayan language.

Before the linemen left on their mission trip, Gayvin Strantz, Indiana Electric Cooperatives vice president of job training, safety and loss control, told them: “This will be both the toughest and the best job you’ll ever have.”

It was. The first week, the team fought dehydration in 100 to 110-degree heat. They did everything by hand — climbing poles using only basic lineman’s gear — gaffs and belts — and digging anchors by hand, with two-handled post hole-diggers. No bucket trucks. No power tools beyond a drill — just stamina and brute human force. Even the bone-jarring, three-hour drive up and down the 2,500-foot mountain each day cost them three days in lost work-time. Impatient to get the job done, the linemen would grumble each morning, “We’re burning daylight. Let’s roll!”

The first look at the staking sheet showed a nearly impossible task to accomplish in 10 days: string 11 miles of wire, connect 76 primary and secondary poles, and secure them with 96 anchors. All by hand.

”When I saw the extent of the work that we had,” said Strantz, “I thought, my land! We’ll be lucky to get half or three-fourths of this done! But it was a pride thing. They wanted to get the project done.”

“We all knew the scale of the task we were given,” remembered Boone REMC’s Michael Shirley. “But we were glad to do it and that brought us together. We just put our heads down and got it done. It was a good bunch of guys.”

The mantra was ‘improvise, adapt and overcome.’

Pat Scheurich, of Jasper County REMC, gets some assistance from local men hoisting a transformer to the top of a pole. The Indiana linemen said the villagers’ work ethic, pride and commitment amazed them.

Photo by Diane Willis

The Project Indiana crew ranged in age from 27 to 60. Dan “Doc” Denu, Dubois REC, plans to retire in 2016 and thought it important to volunteer. “It was the icing on the cake for me. Always before on hurricanes, it was fixing destruction from Mother Nature. This was building something new.”

“I was an Army veteran, deployed twice to Iraq,” said Brian AmRhein, Decatur County REMC. “All I’ve seen there is war. But going to Guatemala, I’ve seen a different part of life. I’ve seen love … and it changed my life.”

“That’s part of the cooperative culture,” added Jeff Conley of NineStar Connect. “We’re always looking for ways to give back and take care of people, to look out for a community. And while we were there, that was our community. They were our customers.”

They never doubted they’d get the job done — and they did in eight days — record time. But during that first week, something changed. Yes, they were still mission-driven. But it also became personal, a matter of the heart.

“For me, it wasn’t life-changing. It was life-humbling,” said Doug MacLain, Marshall County REMC. “Just how happy they were with nothing, it was really humbling.”

“I don’t call myself a hero. I think we did something really neat that was life-changing for the families of Sepamac,” said RushShelby Energy’s Keith Combs. “The friendships built amongst the linemen and the people in the village … I’ll end up taking that to my grave with me.”

“I’ll never forget their work ethic and their appreciation for the littlest thing,” added Rob Blank, Harrison REMC.

After watching Indiana linemen climb poles and string wire in her village, a Guatemalan girl forms a heart with her fingers as an expression of gratitude toward the Americans who came to change their lives.

Photo by Diane Willis

“The people of Sepamac welcomed us with open arms. From day one, they treated us as if we were their family,” remembered AmRhein. A long pause and then he added: “I considered them my family, and I think that’s what made it hard to leave.”

More than anything, it was the children of Sepamac — the mischievous boys and the quiet, gentle girls — who struck a chord. The children left a deep impression: their joy and spirit, the way they followed and watched the linemen, ready to help and play and learn.

“What stuck out about the kids was how happy they were — perpetually happy,” remembered Bruce Berg of Henry County REMC.

“That’s why we did it,” added Conley. “Their parents and grandparents are not going to be there forever. But those kids are going to grow up with that little bit of culture that we bring and instill in them. It was just an amazing feeling.”

They decided to use their last two work days to electrify the local school. But linemen demand more of themselves than anyone would ask of them. They do it on a mountain top — and they do it back home. So, it wasn’t enough they gave of their time. They gave from their wallets, too. In one afternoon, they raised $600, stuffing $10, $20 and $50 bills into a lineman’s hard hat passed around to provide badly needed supplies for the Sepamac School.

Sebastian Coz Coy, 87, is a blind and deaf villager too weak to work. The linemen took up a collection for his family, which includes his wife, Euralia; children; grandchildren; and great grandchildren.

Photo by Diane Willis

Their hearts were also moved by the plight of 87-year old village resident Sebastian Coz Coy, blind and deaf and too weak to work. When the linemen heard the family had nothing to eat, they chipped in to give food, clothes and some cash when the food ran out. “We are so grateful, but we are so very poor,” his wife, Euralia Coy, told us, tears in her eyes. “All we can ask is that God blesses you.”

Would they do it again? You already know the answer.

Almost to a one they agree with Fulton County REMC’s Eric Schlarf’s endorsement — “Absolutely. In a heartbeat!”

“It definitely changed my life for the better. It gave me a sense of accomplishment knowing this group of guys changed a thousand peoples’ lives,” said Scott Sikora, Kankakee Valley REMC.

In the end, it’s not only light that Project Indiana brings — it is life. Hope. Progress. Opportunities. And it brings full circle what happened in the 1930s here in rural Indiana — people working together to light a community, one pole at a time, to make a better life.

On the last day the linemen were in Guatemala, the day the lights officially were turned on before a crowd of 700 villagers, Gavyin Strantz presents a card signed by all the linemen to the Sepamac school principal. Inside the card was nearly $600 the linemen donated by passing a hard hat for badly needed school supplies.

Photo by Jennifer Rufatto

On the last day in Sepamac, when the lights in the school officially were turned on, 700 villagers stood for hours, some in the rain, to mark the moment.

“That’s why we went there for, to give and not receive. We all knew that,” said Denu. “And we got the blessing from them, from day one to the last day we were there.”

Strantz summed it up for everyone that last day, when he told the crowd: “Energy is a bridge for the love we feel, so we can make a better life for you and your children. You’ll forever have a place in my heart and the hearts of these men, in letting us come and help you.”

Diane Willis is a freelance journalist from Indianapolis. She also accompanied Indiana’s line crews on their first trip to Guatemala in the summer of 2012 and wrote the November 2012 Electric Consumer cover story and produced a PBS documentary on that trip. She and her husband, Clyde Lee, who also accompanied the linemen on this trip and shot video, are putting together short videos of the Project Indiana trip. Willis and Lee are former co-anchors of WRTV — Channel 6, the ABC television affiliate in Indianapolis.

• VISIT THE 2017 TRIP TO GUATEMALA

• VISIT THE THE 2012 TRIP TO GUATEMALA

More photos from Guatemala and the homecoming:

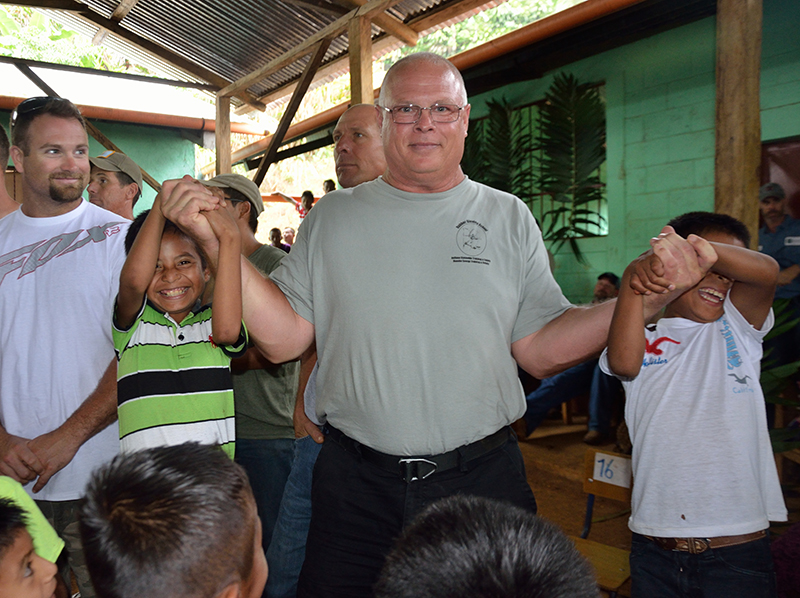

Bruce Berg, from Henry County REMC, greets a youngster at the school during a lunch break. The kids flocked around the Indiana crew each day, and the linemen developed close friendships with them.

Photo by Diane Willis

An elderly woman presses ground corn meal for tortillas in her one-room hut with dirt floors and walls of bamboo poles, typical for the village.

Photo by Diane Willis

“Inauguration Day” was the day the lights were officially turned on at the concrete-block school building.

Hundreds of villagers packed the school building for the lighting celebration — with Indiana’s line crew in the center of it as the guests of honor.

After the power lines were built and energized, field testing was done the day before the official “inauguration day.” The moment the lightbulbs came on in their classroom during a field test, village boys celebrate with a thumbs up and cries of “La luz! La luz.” (“The light! The light.”) Linemen said their proudest moment was seeing the joy on the faces of the children. Photo by Diane Willis

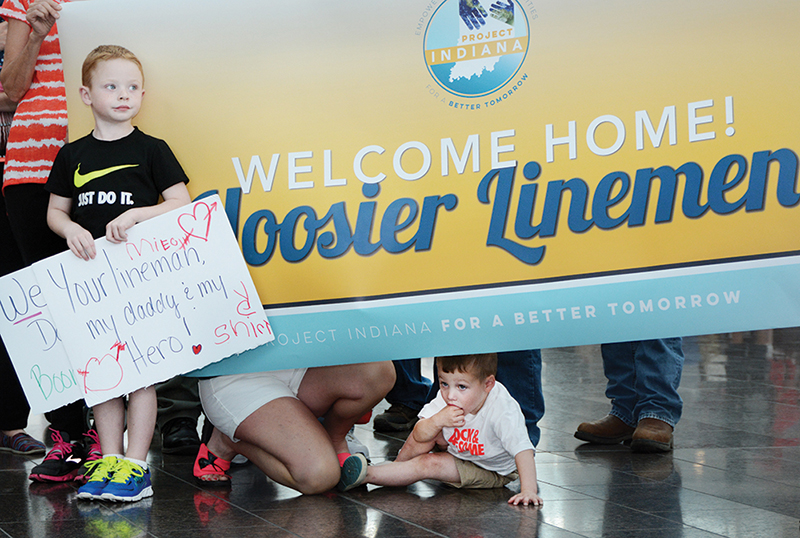

Scores of family and co-op co-workers greeted the linemen as they arrived at Indianapolis International Airport with signs, hugs and kisses after the two-week trip. Among those anxiously waiting for the group to emerge beyond the security gates are Lukas Shirley, left, and his little brother, Gunner, sons of Boone REMC lineman Michael Shirley.

Photo by Richard G. Biever