By Brian D. Smith

You’ve heard the old saying: “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.” But when the state says it has unclaimed property in your name, you can take that to the bank — literally.

One of eight divisions within the Indiana attorney general’s office, the unclaimed property unit distributes more than $1 million weekly to lucky Hoosiers, which might sound like a waste of tax dollars. But in fact, it’s the recipients’ money to begin with, and like the finder of a lost dog, the state is simply helping to reunite it with its rightful owners.

It’s just that with 5.1 million unclaimed property accounts worth a total of $914 million, the job of owner locating is considerably more complicated than responding to a “lost dog” poster. Happily, it’s easier than ever to track down abandoned cash and valuables bearing your name, thanks to the unclaimed property division’s searchable website, indianaunclaimed.gov.

But first things first: What exactly is unclaimed property, and are your odds of finding lost money any better than, say, winning the lottery?

As the attorney general’s office explained, “Any financial asset with no activity by its owner for an extended period is considered unclaimed property. This includes unclaimed wages or commissions, savings and checking accounts, stock dividends, insurance proceeds; underlying shares, customer deposits or overpayments, certificates of deposit, credit balances, refunds, money orders, and safe deposit box contents.”

Your chances of finding unclaimed property in your name are an estimated 1 in 7 — slightly better than the 1 in 292 million possibility of winning the Powerball jackpot. Plus, you can’t go broke trying your luck in the unclaimed property giveaway since it costs nothing to search online.

The highest claim paid this year was a whopping $750,000 — the state won’t identify the recipient — and even an average claim amounts to $1,018. But in the interest of managing expectations, it’s useful to remember that three-fourths of all accounts contain $100 or less.

And some low-end claims aren’t worth the cost of mailing the check, such as the 50 cents awaiting a citizen of Pendleton, Indiana.

Still, whether it’s $20 or $50 or “over $100” — as the state’s online search engine describes any sum above the century mark — it’s never a bad day when you learn that you’re entitled to money you didn’t even know you were owed. An Indianapolis woman discovered as much when the search engine matched her name to a $248 check from an insurance company that she couldn’t even remember doing business with.

Keep in mind that not all unclaimed property comes with a dollar sign. Abandoned safe deposit boxes surround all manner of colorful cargo, including jewelry, rare coins, and collectibles, not to mention the occasional personal item — sometimes too personal.

Through the years, the state has taken possession of such items as false teeth, locks of hair, steamy love letters, and even ladies’ undergarments.

On a historic note, forgotten safe deposit boxes in Indiana have held Civil War discharge papers and a lapel pin from Lincoln’s inaugural ball. And in 1985, the state received some of the ultimate unclaimed property — the never-returned contents of safe deposit boxes from 15 Indiana banks that failed during the Depression.

All tangible items of value that remain unspoken for are auctioned off, with one exception: the state does not sell military medals.

Almost 60 years of returning assets

If searching for abandoned cash sounds like an exciting new endeavor, you might be surprised to hear that unclaimed property is neither new nor unique. According to the attorney general’s office, every state maintains a central location where people and businesses can search for long-lost assets. Indiana got in the game in 1967 when lawmakers passed a bipartisan bill giving the state the authority to collect abandoned property from banks, insurance companies, utilities, and other businesses. Though their actions would make thousands of residents a bit richer, their motives were not entirely altruistic.

The chief priority was to replenish Indiana’s Common School Fund for public school construction, which had run out of cash.

Although the state attempted to notify the rightful owners by running legal advertisements in newspapers across Indiana, no one seriously believed that most of the money would ever be returned. Proponents of the bill predicted it would generate millions of dollars, and sure enough, Indiana Attorney General John J. Dillon reported in 1968 that the state had collected $3.3 million worth of unclaimed assets and expected to have $2.8 million left over for the school fund.

Legal ads served as the first notifications for owners of unclaimed property, but evolving technology has given the state more ways of connecting Hoosiers with their lost money. In 1988, an unclaimed property exhibit at the Indiana State Fair featured a computer that offered free searches for fair-goers. In 1994, the database went online, though in a primitive form.

More recently, the unclaimed property website has offered not only searches but also the ability to stake claims with the click of a mouse. And in 2021, tangible property started going on the online auction block on eBay.

Three “Cheers” for a long-awaited settlement

Perhaps the most famous unclaimed property owner in Indiana history was also the most persevering. It started in 1973 when a Fort Wayne girl’s long-inactive school savings account at Lincoln National Bank wound up with the unclaimed property division in Indianapolis. An inquiry by the girl’s mother, Ivadine Long, brought her a claim form, but it seems she never returned it. A year later, the same bank forwarded another dormant school savings account, also bearing the name of Ivadine’s daughter, Shelley Lee.

That’s right: The two savings accounts, totaling $247.06, belonged to future “Cheers” star Shelley Long.

But she wasn’t famous for anything in 1975 when she decided to contact the attorney general’s office about recovering her lost money. Then living in Evanston, Illinois, she signed her name “Shelley Long Solomon,” having wed for the first time four years earlier. After receiving a claim form, she completed it and sent it back, but her trek through a tangle of red tape was only beginning.

The state repeatedly moved the goal posts, first demanding a marriage certificate because her last name had changed and then, after receiving such proof in 1977, insisting it now needed a passbook with a guaranteed signature, a bank card, or an affidavit from a third party connecting her to the property, and photocopies of both notary public commissions.

It would be another seven years before the unclaimed property division heard from the Fort Wayne native again. By that time, Shelley Long was an Emmy Award-winning actress with a return address of Paramount Studios in Los Angeles, and her letter was the talk of the Statehouse. She found a more sympathetic ear from division director Calvin Kuhn, who approved her request after she submitted a notarized claim form. A $247.06 check payable to Shelley Lee Long was sent on Oct. 3, 1984 — six days after the start of the third “Cheers” season.

Obtaining your property

How does an unclaimed property search work?

Following the previously provided link to the Indiana Unclaimed website, you will see a gold rectangle containing the words “Claim yours” on the right side of the screen. Clicking on that rectangle takes you to a different screen with the heading “Search for unclaimed property” and a form with five blank spaces.

There is no need to fill in every blank — one keyword or number in the first space (“Last or business name”) is enough to get the search engine running. But unless you have an uncommon surname or business name, you should add a first name or zip code; otherwise, you will be dealing with a parade of page numbers at the bottom of the screen. For instance, “Smith,” “Jones,” and other common names span 50 pages with 20 claims per page, whereas “Superman” returns just a single claim.

Your search needn’t end with your own name. If you want to help a good cause but are too lean in the green to contribute, you can arrange a “non-donation” of sorts. Just plug in a name or term representing a church, organization, or interest, browse the claims for any groups you support, and contact your favorites with news of their unforeseen bounty. For example, searching for “church” begets Morningside Church of Evansville and “over $100” for the collection plate. The words “animal shelter” fetch Rushville Animal Shelter and the $50 it’s due, whereas “band” strikes up a list of eight and possibly 11 modest claims meant for the Frankton (High School) Band Boosters.

Naturally, you can try to give your friends and family a little wallet widening by running their names through the search engine and looking for any reflections.

Maybe you’ll even enjoy the process. With an index of claims and property owners ranging from “AAA AAA” to “ZZZ Legal,” Indiana’s online lost-and-found department offers infinite possibilities to explore.

But if the Hoosier State’s unclaimed universe ever leaves you longing for new horizons, you can always take it to the next level.

For those with out-of-state connections, whether business or personal, MissingMoney.com — the official unclaimed property website of the National Association of State Treasurers — boasts multiple-state searches, $3 billion in paid claims over the past year, and an average claim value twice as high as Indiana’s.

What better place to seek claim and fortune?

The mysterious case of Sejdo Ustavdic

Of the 5.1 million unclaimed property accounts in Indiana, none has a more mysterious owner than Sejdo Ustavdic. In 1989, before the state stopped publishing the exact value of accounts exceeding $100, he ranked No. 1 on the most-owed owner list with an abandoned bank account of $38,320.08.

Today, Sejdo Ustavdic has 129 accounts containing savings bonds valued at “over $100” apiece. Simple math tells us they’re worth at least $13,000 and perhaps more – especially if they contain any of the $38,000 from 35 years ago. Then again, these accounts weren’t reported until 2016.

Whatever the origin, it’s a lot of money to leave behind. So who was Sejdo Ustavdic, and why hasn’t he, or his heirs, come to collect the thousands of dollars he’s entitled to?

Unclaimed property records say only that Ustavdic once lived at a couple of addresses in Gary. You have to look farther, across two continents and an ocean, to uncover the surprising — and surprisingly poignant — story of his life. Although all such research runs the risk of confusing identically named individuals, the records uncovered in this case seem to point to the same person.

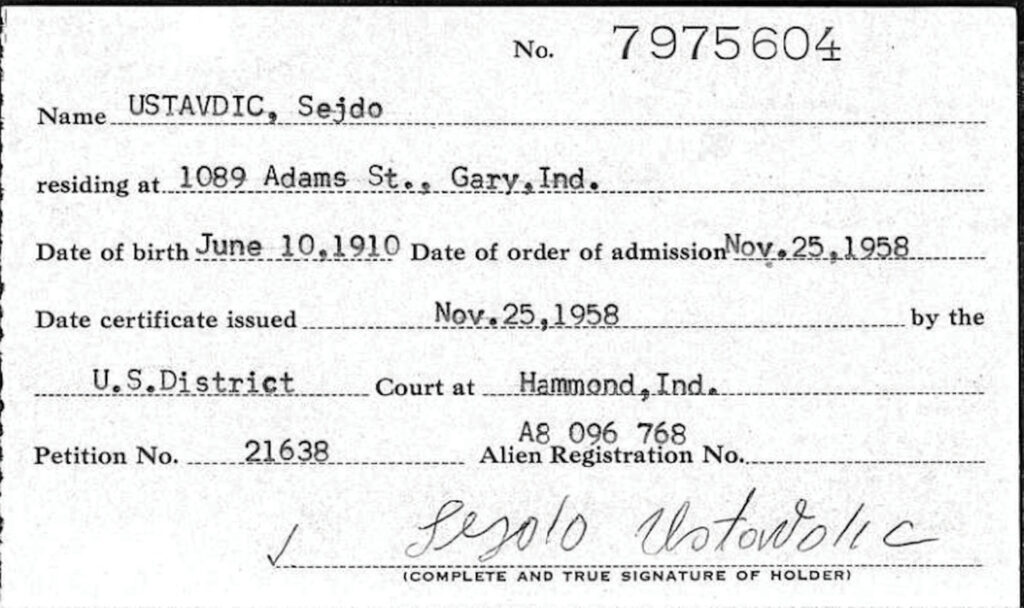

A search on Ancestry.com returns two documents, including the 1958 naturalization record of a Sejdo Ustavdic, who was born in 1910, lived in Gary, and took his oath of citizenship at the U.S. District Court in Hammond.

The second document, a yellowed ship’s passenger list, notes that on August 21, 1951, a 41-year-old single man named Sejdo Ustavdic — born “about 1910” — journeyed from Bremerhaven, Germany, to New Orleans on the U.S.S. General Taylor.

But this was no routine voyage. The document came from the Arolsen Archives, known as “the largest archive on the victims of Nazi persecution,” and the ship was carrying war refugees to freedom. As the National WWII Museum website explained, “After World War II, 1.2 million Eastern European displaced persons remained in Germany and refused to return home.” Many feared living in nations now trapped behind the Iron Curtain of Soviet influence.

A “displaced persons statistical card” from the same archives reveals even more about Ustavdic’s life. He

was born in Austria-Hungary, which became Yugoslavia after World War I, and he spoke Croatian (thus, his first name would have rhymed with “Play-Doh”). He was an unskilled laborer who had worked as a farmhand, fruit picker, and shoemaker.

How he became a displaced person is not written. It’s possible that he lost family members in the war or was imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp, even though his religion is listed as “Mosl” — a likely abbreviation for Moslem, the archaic term for Muslim.

Regardless, what the statistical card tells us is sad enough: He entered Austria in September 1945 — the month World War II ended — and lived in a refugee facility known as Camp Wegscheid. The Jewish organization ORT said Wegscheid was “seriously overcrowded and did not have anywhere near enough living space. There were also problems with inadequate food supplies and quality.” Yet Ustavdic apparently spent all or part of six years there before finally getting permission to come to America.

What happened to him after his 1958 naturalization ceremony is untold. Did he find work in Gary’s steel mills and stash away most of what he earned, only to die before he could spend it? Did he leave behind only distant relatives in Europe?

The answers remain elusive. But if it means anything, there’s a vacation rental on the Croatian island of Korcula featuring kitchenettes, a private entrance, and balcony views of the Adriatic Sea. Its name is Apartments Ustavdic.

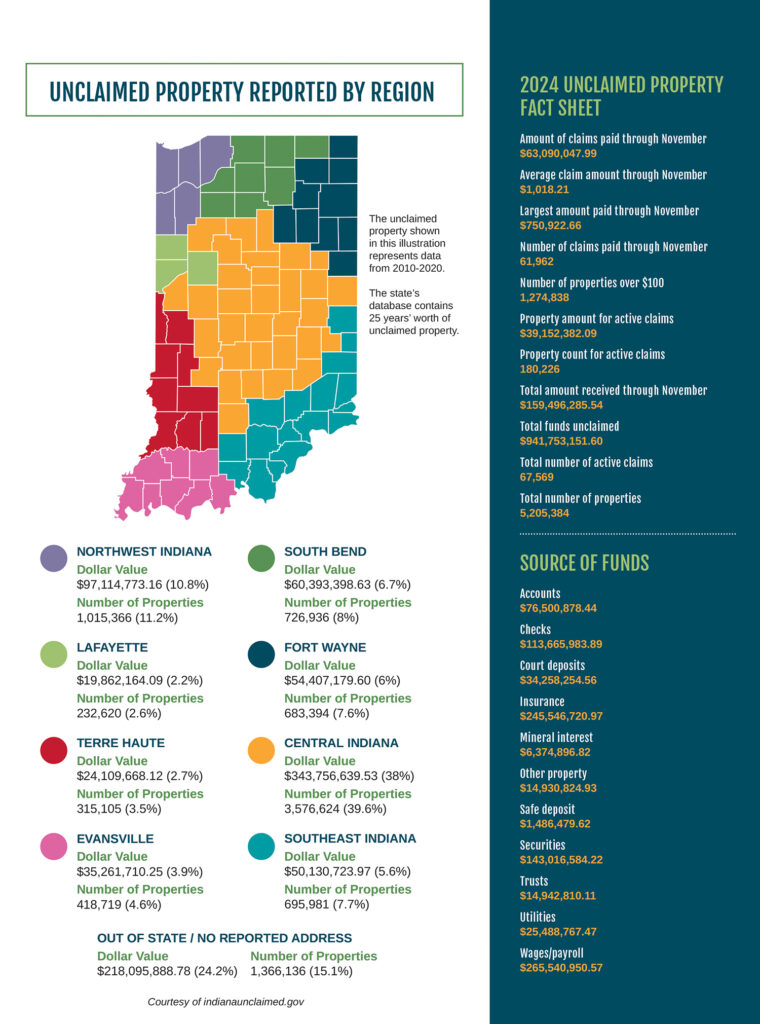

UNCLAIMED PROPERTY REPORTED BY REGION