“The last miracle I did,” said God (portrayed by comedian George Burns in the 1977 movie, “Oh, God”), “was the 1969 Mets. Before that, I think you have to go back to the Red Sea.”

Whether the “Miracle Mets” received divine intervention or not, one thing is for sure: the 1969 World Champs did have a Moses. Parting the major leagues and leading the put-upon New York Mets to the promised land was manager Gil Hodges, the former Dodgers star and native Hoosier.

“He’s the guy who made the difference between being World Champions and a second-rate ball club,” Cleon Jones has said of Hodges. Jones was the Mets star left fielder who caught the final out of that World Series against the Baltimore Orioles. “We would have been real happy to finish second. But he wasn’t satisfied with that.”

The 1969 Mets is still one of the greatest Cinderella stories in baseball’s 150 year history. The Mets were 100-to-1 shots coming into that spring, but the 7-year-old laughable doormats blew past the fading Chicago Cubs and swept the Atlanta Braves to win the pennant. After dropping the opening game of the World Series, the plucky Mets deplumed the heavily favored Orioles in the next four straight games.

The 50th anniversary of that 1969 season will be among the story lines repeated this year. And one thread certain to run through each retelling will be crediting Hodges — Petersburg, Indiana’s favorite son — for flip-flopping the Mets’ fortune.

Members of that team, which included future Hall of Fame pitchers Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan, have said it was the steady leadership of Hodges — an ex-Marine — who instilled the professionalism and work ethic they needed to win; it was Hodges who gave them the heart and mind to think they could win.

From a coal miner’s son to a ‘boy of summer’

Hodges was born in Princeton, Indiana, April 4, 1924. The son of a coal miner, he grew up in Petersburg. After graduating from high school in 1941, Hodges played baseball at St. Joseph’s College in Rensselaer and, in 1943, was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers. He played in one game for the Dodgers that summer. Then, World War II intervened. Once the war was over, his baseball career resumed.

In the summer of 1947, he and another rookie, a guy by the name of Jackie Robinson, joined the Dodgers in Brooklyn. Within just two seasons, Hodges was considered one of the finest first basemen and hitters in the league.

He was one of Brooklyn’s great beloved “Boys of Summer” alongside Robinson, Duke Snider, Pee Wee Reese, Roy Campanella, and pitcher Carl Erskine, a fellow Hoosier from Anderson.

Hodges was an eight-time All Star and played in seven World Series, six for the Dodgers in Brooklyn and the last after the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles.

From doormats to ‘Miracle Mets’

After the 1961 season, Hodges was drafted by the expansion Mets, a new National League team that would begin play in 1962. The Mets were created to help ease the heartache New Yorkers felt after both of New York’s National League teams, the Dodgers and the Giants, left for the West Coast after the 1957 season. Hodges was the Mets starting first baseman in their inaugural game.

But the Mets were built around beloved ballplayers — like Hodges — who were past their prime but could still draw in New York fans. They were managed by colorful former Yankees skipper Casey Stengel.

The team’s chemistry exploded like a high school stink bomb, and they became an old-timer’s sideshow. That 1962 team lost 120 games, the most by any team in modern baseball. Stengel dubbed them “The Amazin’ Mets” and they became lovable losers.

Hodges played in 11 games for the Mets in 1963 before moving to the Washington Senators. He then retired as a player and became the Senators manager.

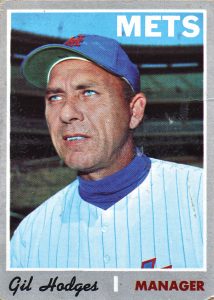

In 1968, the Mets lured Hodges back to New York. This time it was to manage the still lowly Mets. The Mets had risen to ninth place in the 10-team league only once. But now, the Mets had strong young talent, especially its pitching staff. They needed a mentor.

Hodges, with his knowledge and respect for the game and his calm but firm and professional demeanor, his Lincoln-like self-deprecating humor, perfectly filled the bill.

Hodges had no bigger fan than Seaver, the team’s franchise pitcher. “The one guy who taught me how to be a professional,” Seaver said at his Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 1992, “ … Gil Hodges … the most important man in my life from the professional standpoint of my career. And, God, I know that you’re letting Gil look down on this today, and I know that he is a part of this.”

Though the 1968 Mets finished ninth that year, their 73 wins was a franchise best. Then came 1969.

The 1969 season was another expansion year for baseball. To accommodate two new teams in each league, both leagues divided into two divisions. A post-season playoff series for the first time would determine the American and National League pennant winners. Despite the added opportunity the new league configuration presented, the Mets imagined only breaking even for the first time ever.

“There was no talk in spring training about winning a pennant because that’s unrealistic,” recalled Ed Kranepool, who was only 24 at the time but had been with the Mets since their first season. “Going from last place to first place? You got to take small steps.”

But like astronaut Neil Armstrong’s last step from the ladder of a lunar lander a quarter million miles away that same summer, one small step for man became a giant leap …. Way back in the Mets early days, Stengel predicted men would land on the moon before the Mets would win the World Series. He was right — but only by three months.

Hodges legacy

The Mets finished third in the NL East with identical 83-79 records in 1970 and 1971. Then, on April 2, 1972, after playing golf with his coaching staff during the first baseball player’s strike that delayed the start of the season, Hodges suffered a massive heart attack. He died in the arms of coach Joe Pignatano, two days shy of his 48th birthday. He was buried in Holy Cross Cemetery in Brooklyn.

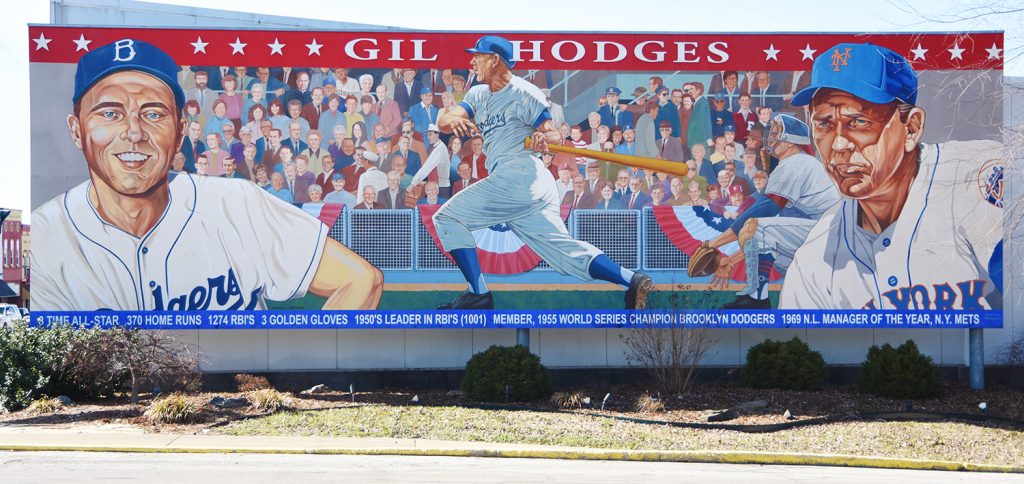

In his hometown, Hodges is still cherished. Across the street from the Pike County Courthouse, a giant mural celebrates his baseball career. It’s a reminder that Hodges is the greatest ballplayer — with that miracle World Series win as a manager — not in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Inside the courthouse, a larger-than-life bronze bust of Hodges is on the main floor with a plaque that reads in part: “Gil was a man of integrity, dignity, community, family and God. He never forgot where he came from, and we will never forget him.”

State highways converge at that intersection with the mural and courthouse. Coincidentally, the highway numbers — 57 and 61 — on the signs hanging from the gantry next to the mural coincide with years significant in Hodges’ career:

• 1957 was the last season the Dodgers played in Brooklyn;

• 1961 was the last season Hodges played with the Dodgers.

Now, posted beside those markers on that gantry is a new blue and red interstate shield with an arrow. It points to Indiana’s newest interstate that passes just to the east of Petersburg. It’s another coincidental tip of the cap to Hodges and his incredible baseball career. That sign says: “To 69.”

“Sometimes it takes a special leader to create special events,” Jones, the Mets outfielder, added about his mentor and that miracle season. “Any other manager … we wouldn’t be talking about the ’69 Mets.”

Hoosiers were top of the heap in New York, New York

Anyone who follows baseball and football and their history might be aware of the similarities of this year’s 50th anniversary Super Bowl and World Series champs.

The New York Jets won Super Bowl III in January of 1969; the New York Mets won the World Series in October of 1969. Besides being from New York, having rhyming names, and originating in the early 1960s, both teams handily beat heavily favored teams from Baltimore. The Jets and Mets championship upsets over the Colts and the Orioles are still considered by many the most surprising upsets in the history of either sport.

But what many folks may not realize: like Gil Hodges of the Miracle Mets, the head coach of the Jets was also a native Hoosier. Weeb Ewbank was born and grew up as a multi-sport high school star in Richmond, Indiana. He went on to star at Miami University in nearby Oxford, Ohio. Before beating the Baltimore Colts in 1969, he won back-to-back NFL championships a decade earlier as head coach of the Colts.