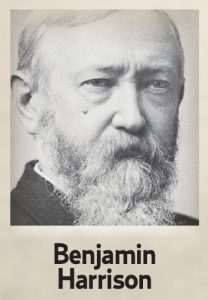

While Indiana has been the home of five U.S. vice presidents (and potentially a sixth in the making with Gov. Mike Pence on the ticket Nov. 8), the state has had only one resident elected president. That was Benjamin Harrison, who served from 1889-1893. In his four years, Harrison left lasting legacies, including one of light.

Indiana’s only resident president, Benjamin Harrison, embraced bright, bold ideas in the White House. Many of his policies put the nation on course for the 20th century.

But his campaign of 1888 was low key -— especially by today’s never-ending campaign standards. He was elected without hardly leaving his home in downtown Indianapolis.

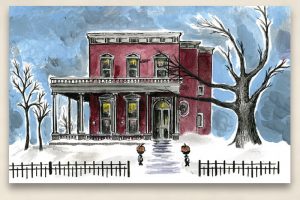

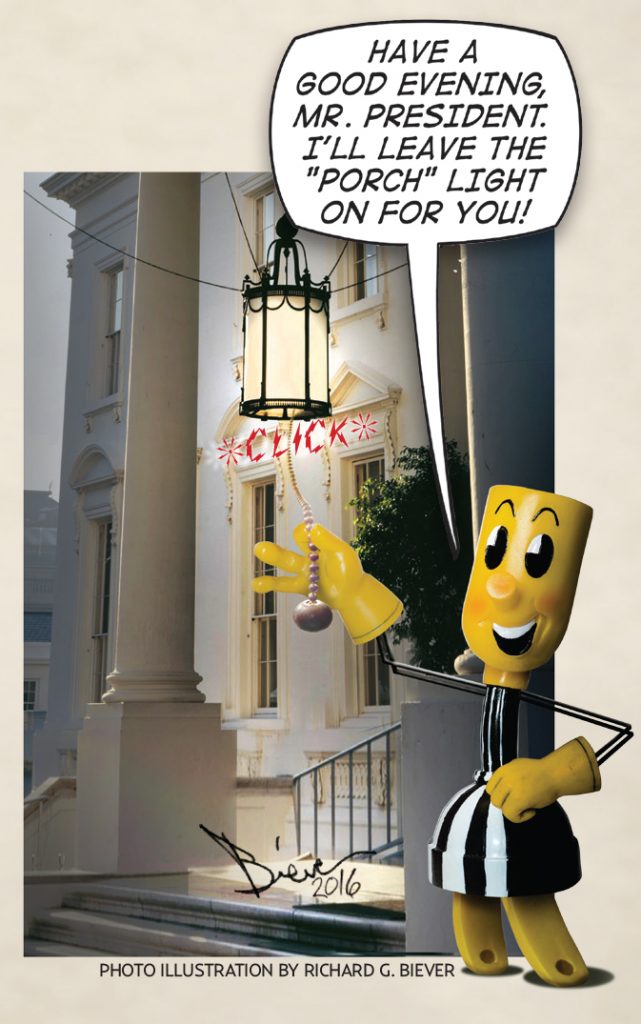

Instead, he’d give impromptu political speeches to large and small delegations as they’d come by. This “Front Porch” style of campaigning was used by a handful of candidates with some success up to 1920. As a tidbit of history, though, Harrison’s Italianate-style mansion didn’t even have a front porch at the time. “It really was just a front stoop,” said Jennifer Capps, curator at the home which is preserved as a museum, memorial and a venue for small events. (The wrap around porch on the home was added in 1895 after Harrison returned to Indianapolis when his presidency ended.)

Instead, he’d give impromptu political speeches to large and small delegations as they’d come by. This “Front Porch” style of campaigning was used by a handful of candidates with some success up to 1920. As a tidbit of history, though, Harrison’s Italianate-style mansion didn’t even have a front porch at the time. “It really was just a front stoop,” said Jennifer Capps, curator at the home which is preserved as a museum, memorial and a venue for small events. (The wrap around porch on the home was added in 1895 after Harrison returned to Indianapolis when his presidency ended.)

Porch or not, Capps said some 300,000 people stopped by Harrison’s home from July 7 through Oct. 25 of 1888 to hear him make more than 80 campaign speeches.

Like folks today, these crowds must have been eager for souvenirs. But with no gift shop to visit or selfies to take, they swiped the pickets from Harrison’s oak fence instead. People also destroyed the lawn. Harrison’s wife, Caroline, quipped if they didn’t make the White House they’d be in the poor house.

Benjamin Harrison’s Indianapolis home is the subject of an honorable mention-winning painting by Laurabeth Landis in the Cooperative Calendar of Student Art 2017, now available at participating electric co-ops or by mail (see page 17). The home is open as a museum and celebrates the 23rd president’s legacy as the Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site. For information about Harrison, visit: http://www.bhpsite.org.

Harrison was the grandson of the ninth president, William Henry Harrison, who also had strong ties to Indiana as governor of the Indiana Territory (1801-1813) and victor in the Battle of Tippecanoe, Nov. 7, 1811, over a confederation of Native Americans. Harrison County is named for him. William Henry Harrison then became a politician in Ohio. He was elected president in 1840. He became ill and died a month after taking office in 1841.

Benjamin Harrison was born near Cincinnati in 1833. After moving to Indianapolis in 1854, he immersed himself into the newly-formed Republican Party while developing a reputation as a brilliant lawyer. Harrison was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1880. He served one term.

On Nov. 6, 1888, Harrison defeated the Democratic incumbent, President Grover Cleveland. He took the presidential oath on March 4, 1889. His administration oversaw an ambitious agenda. Among his accomplishments during his term, Harrison:

- began modernizing the U.S. Navy;

- built up the national parks and forests;

- signed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, the first

to limit monopolies; - advocated for a more organized and selective immigration policy;

- opened working relationships with Central and South American nations as part of a broader emphasis on foreign policy.

In the meantime, Congress approved a needed renovation of the White House requested by the First Lady. Among the improvements was the installation of newfangled wiring and electric lights.

In May of 1891, the Edison Company oversaw the installation of “incandescents” in the White House and the State, War and Navy Building next door (today’s Old Executive Office Building). A generator for both buildings was installed in the State, War and Navy’s basement.

Many of the White House gas chandeliers and fixtures were converted to accommodate both electric and gas. The relatively new method of illumination was initially intended to be only a supplement to gaslight. Wires were buried in the plaster, with round switches installed in each room for turning the current on and off. Though the Harrisons showed great interest as the work progressed, they never touched the light switches themselves for fear of being shocked. This was a reasonable fear at the time, given how crude household electric wiring could be just 10 years after Edison’s lightbulb was perfected. The domestic staff was in charge of turning the lights on and off.

One of the men installing the wiring was 19-year-old Irwin H. Hoover, known as “Ike.” In his memoir, Hoover recalls, “In due time I got down to the job of wiring and installing the electric appliances. The wonderful old chandeliers, built for gas, were converted into combination fixtures and the candle wall brackets were replaced by electric fixtures in the fashion of the time. The Harrisons were all much interested in this new and unusual device that was being installed; so much so, that we got quite well acquainted with them.”

One of the men installing the wiring was 19-year-old Irwin H. Hoover, known as “Ike.” In his memoir, Hoover recalls, “In due time I got down to the job of wiring and installing the electric appliances. The wonderful old chandeliers, built for gas, were converted into combination fixtures and the candle wall brackets were replaced by electric fixtures in the fashion of the time. The Harrisons were all much interested in this new and unusual device that was being installed; so much so, that we got quite well acquainted with them.”

The Harrisons got to like Hoover so much, he was offered full-time employment as White House Electrician after the installation was done. He hesitated to take the job because the salary was so low, but accepted the offer and became, “like the electric lights, a permanent fixture,” he later wrote. Hoover spent 42 years working at the White House, advancing from electrician into the ushers’ ranks. During the Taft administration he was appointed Chief Usher, and he held this job until he died in 1933.

It’s also believed Harrison was also the first president ever to have his voice recorded — using Edison’s wax cylinder — in 1889.

By the 1892 election, a souring economy and rising prices on goods turned the public against Harrison and the Republicans. Also, two weeks before the election, Caroline died of tuberculosis, and the presidential campaigns closed on a sad, somber note. Cleveland was elected to become the only president to ever serve two non-consecutive terms.

Harrison returned to his Indianapolis home. He remarried and had the home updated — and wired, as well — in 1895. He died in 1901, but not before fathering a son by his second wife.

Along with his forward thinking, another bright legacy it can be said the 23rd president left … was the lights on in the White House for all the presidents who have followed.

Join us next month as Willie presents the last of his Indiana “Bicentennial Zingers.”